GPS can tell you how to get just about anywhere on the face of the Earth. It’s no good, however, beyond the borders of reality. For that kind of journey, a map will do a better job of guiding the way.

The Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education makes that case with its latest exhibition, “North of Nowhere, West of the Moon: Myth, Fiction, and Fantasy in Maps.” Rather than mapping a real place, most items on display depict places that can only be visited through the viewer’s imagination.

“Especially as we’re entering the third year of the pandemic, we designed this intentionally as an escape,” said Libby Bischof. “We crafted this gallery experience to give people a minute from their life to step away into these other worlds. And I hope that people will take advantage of that opportunity and just give themselves kind of a mental break from everything that’s going on around us even if it’s only temporary.”

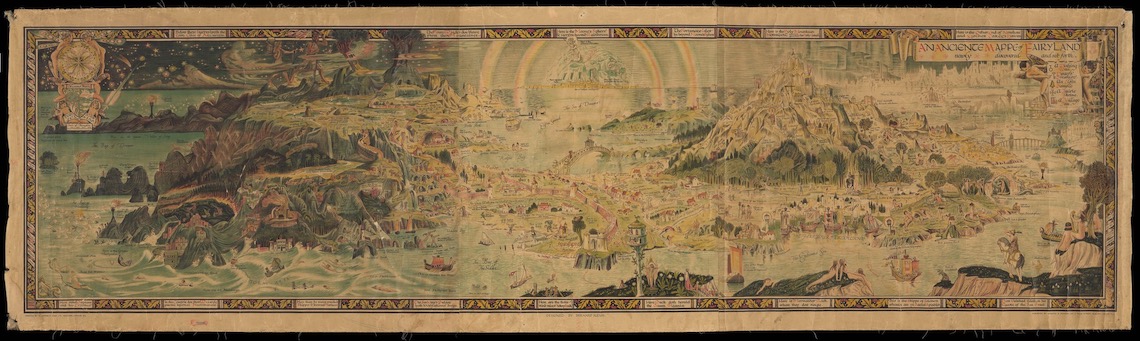

Bischof is Executive Director of the Osher Map Library. She hatched the idea for the exhibition following the recent acquisition of Bernard Sleigh’s “An Anciente Mappe of Fairyland.”

For some do hold our Arthur cannot die,

But that he passes into Fairyland.

— Idylls of the King by Alfred Lord TennysonSleigh was a muralist and, at six feet in length, the map reflects his talent for working on a large scale. His landscape combines elements of folktales, mythology, and literature spanning centuries. It imagines a world where Snow White might cross paths with Hercules or King Arthur. Created in 1918, the map offers a whimsical counterpoint to the brutality and cynicism of World War I.

Bischof wanted to spotlight Sleigh’s map by showing how it fit into a tradition of charting imaginary places. She looked inward at Osher’s collection of nearly half a million cartographic items. The library is especially well-known for its historic maps dating back to 1475. As the exhibition took shape in her mind, Bischof saw an opportunity to bring the library’s 20th century holdings into the forefront.

“As someone who studied a lot of art history, I’m a photo historian, these maps to me are just beautiful,” Bischof said. “I think there’s just so much color, there’s so much design. I think aesthetically, they’re going to really appeal to a lot of people, too.”

She asked where he lived.

“Second to the right,” said Peter, “and then straight on till morning.”

“What a funny address!”

— Peter Pan by J.M. BarrieExhibitions usually take a year or more to research and organize before the public gets to see them. Driven by the urgency of Bischof’s vision, “North of Nowhere” came together in the relatively short span of two months.

The two earliest maps in the exhibition depict the most up-to-date understanding of world geography for the 16th and 17th centuries. In areas where knowledge was limited, the mapmakers filled the gaps with their assumptions about the waterways, and land masses that were surely waiting to be discovered. Monsters and mermaids were often shown to be standing guard over those unknown regions. Fantasy, we’re shown, was always part of the mapmakers’ trade.

Books like “Peter Pan” by J.M. Barrie give mapmakers permission to let their imagination run wild far beyond the embellishments of those earlier maps. Several maps in the exhibition depict Never Never Land, replete with Captain Hook’s pirate cove and the underground hideaway of the Lost Boys. The different arrangements of those landmarks show how widely interpretations of the same source material can vary between mapmakers.

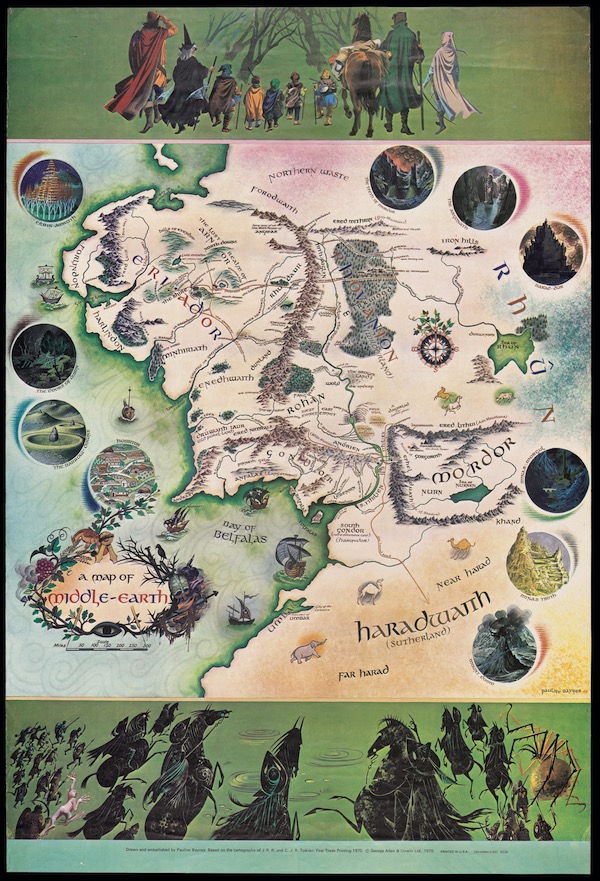

The whimsical, painterly renderings of Never Never Land contrast with the nearby maps of Middle Earth, which could easily be mistaken for actual historical documents. A familiarity with cartography is evident in the technical precision of the coastlines and mountain ranges. As a companion to “The Lord of the Rings,” the map strives to reach a level of authenticity in keeping with J.R.R. Tolkien’s words. He invented entire languages and genealogies in service to his goal of transporting readers into an alternate version of history.

“I’ve often lost myself in the worlds of a novel ever since I was very young,” Bischof said. “Reading has always been a pretty distinct escape for me. And my appreciation of this particular show and some of the items within it really come from that.”

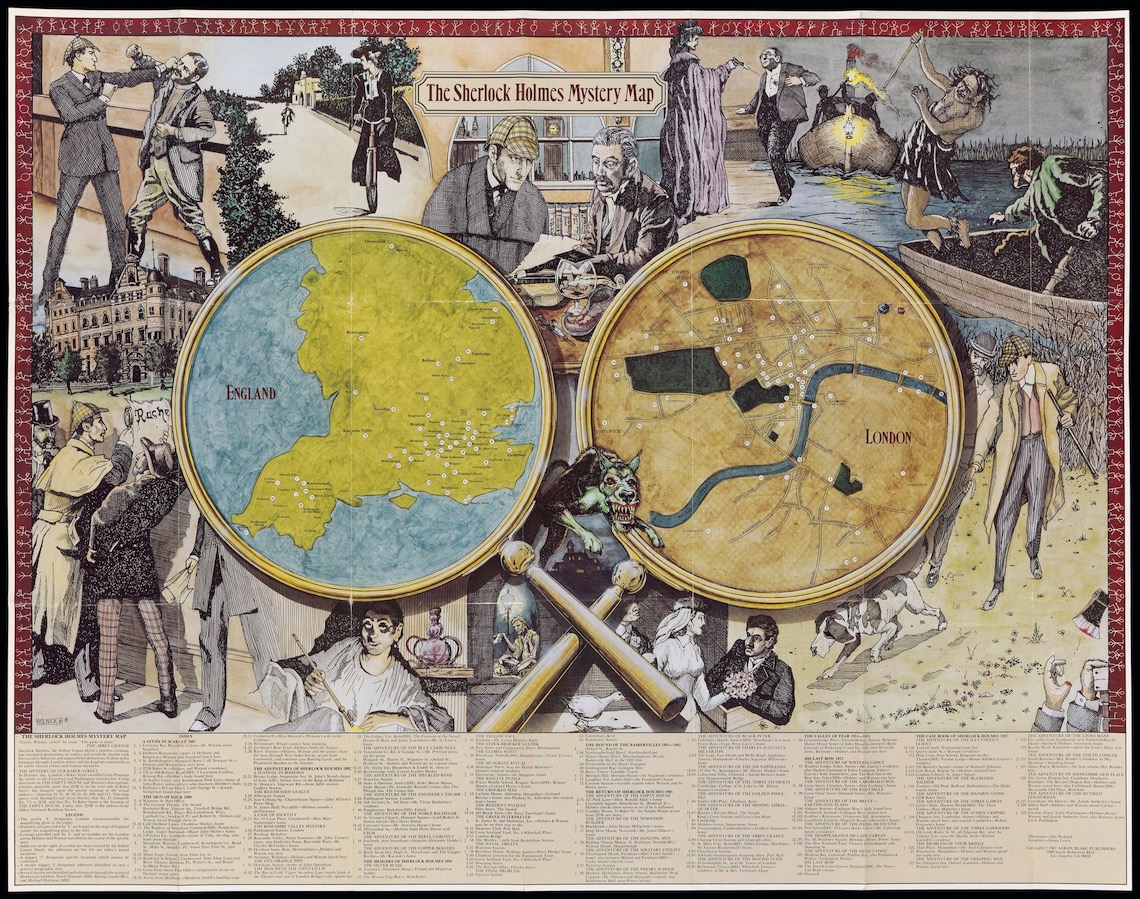

Writers like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle pose a different challenge for mapmakers. He imagined the real streets of London as a playground for his fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes. The line between reality and fantasy became so blurred that some readers believed Holmes really existed. A map in the Osher Library’s reading room indulges that belief by charting key locations from Holmes’ adventures across London as well as the rest of England.

“It is my belief, Watson, founded upon my experience, that the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.”

— The Adventure of the Copper Beeches by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The whole world and all of fiction receive that same treatment from “The Atlas of Imagined Places: From Lilliput to Gotham City.” Its writers spent years compiling a list of 5,000 fictional places and pinpointing their real-world locations. Their sources spanned novels, movies, television shows, pop music, video games, comic books and more. They filled 168-pages with maps that looked at once entirely familiar in shape but utterly fanciful in detail.

The atlas hit many of the same notes that Bischof was trying to achieve. As a companion to the exhibition, she arranged for the writers to explain their mapmaking process in a lecture hosted by the Osher Library. Matt Brown, Rhys Davies and Mike Hall spoke from their homes in England via Zoom to an online audience on January 22.

“We had very serious rules which we go into in some depth in the introduction,” Brown said, “and then we broke most of those rules when we found really interesting or fun examples that broke the rules in some way.”

One of the biggest rules that Brown and his co-authors followed was that only places with names could be included. They also required at least a basic hint of direction to make it mappable. Some places were easy to locate like the setting for the animated movie “The Iron Giant” which gave precise coordinates for Rockwell, Maine. That was one of the more lighthearted entries when compared to surrounding towns.

“It is in New England what we find what H.P. Lovecraft described as ‘the true epicure of the terrible,’” said Davies. “And as can be seen from a glance at our map, New England is indeed the home of the horrible.”

Many of Maine’s entries like Jerusalem’s Lot, Derry and Castle Rock were dreamed up by horror novelist and Bangor resident Stephen King. The Maine coast is also home to Cabot Cove, as the setting for the TV series “Murder, She Wrote.” From there, Whipstaff Manor is just a short drive away. It’s haunted by Casper, the Friendly Ghost, whose adventures span movies, cartoon shorts, and comic books.

“Who are you?” asked the Scarecrow when he had stretched himself and yawned. “And where are you going?”

“My name is Dorothy,” said the girl, “and I am going to the Emerald City, to ask the Great Oz to send me back to Kansas.”

— The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

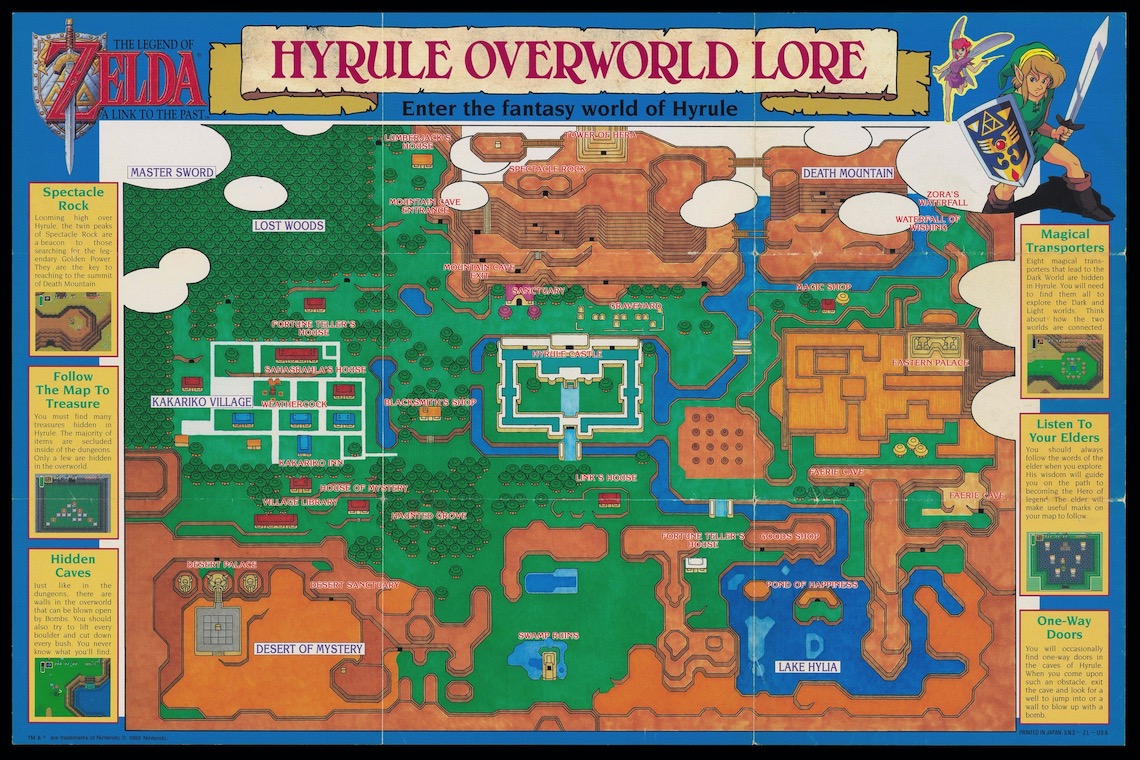

Like the atlas, the exhibition took an all-inclusive approach to its sources. The gallery walls include maps inspired by the Zelda video game series, the Disneyland amusement park, and the Candy Land board game.

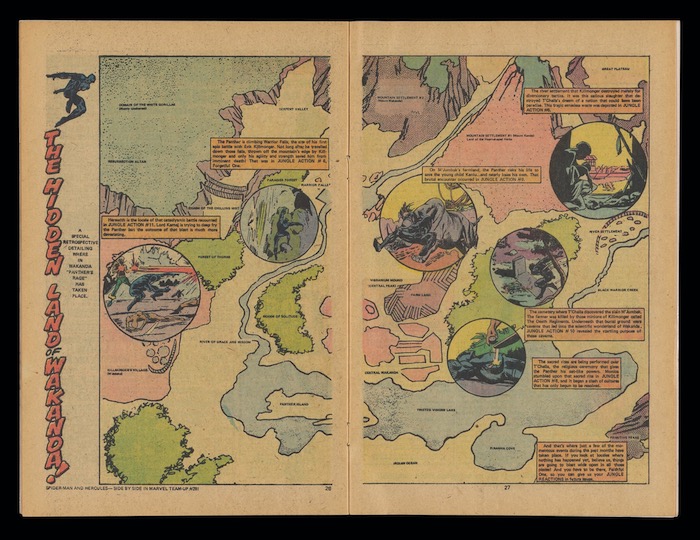

When a subject spans multiple media, mapmakers are faced with a choice. They can select a single version as the basis for their map or try to reconcile between the different interpretations. Certain details in the famous “The Wizard of Oz” movie from 1939 differ greatly from the book upon which it was based. Those kinds of discrepancies are multiplying as superhero movies continue to proliferate. A map of Wakanda that was drawn for a comic book in 1973 looks much different from the way it appeared in the 2018 movie “Black Panther.”

The kids may come for the superheroes, but the exhibition tries to build off that interest by appealing to their innate sense of adventure and creativity. The Osher Library will host two workshops on March 19 and 26 to give kids tips on making their own fantasy maps. Other kids are credited as artists in the exhibition. A glass case in the center of the gallery features submissions to the library’s annual mapmaking contest which is open to Maine students in Grades 4-6.

“We find that kids are really good at it,” Bischof said. “We hope that the kids who come and see this exhibition are really inspired by what they see to create their own maps.”

“Why do you sit out here all alone?” said Alice, not wishing to begin an argument.

“Why, because there’s nobody with me!” cried Humpty Dumpty.

— Through the Looking Glass by Lewis CarrollThe exhibition opened on January 20 and runs through May 30. Admission is free, but visitors must contact the library to book a time for their tour. The library is open Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.