Tackling your summer book list in a college classroom rather than on a beach probably isn’t the first choice for most kids. Sympathetic teachers are doing their best to make those summer reading lessons as fun as they are educational.

Sarah Mills keeps a pack of Uno cards handy. Her students play the game at snack time to unwind after working hard to sound out words all morning.

“They’re being good sports about it and trying to figure out ways to enjoy the moment and enjoy what we’re doing,” Mills said.

Mills knows how to connect with kids having worked in educational settings for 19 years, most recently as a Literacy Educational Technician (Ed Tech) in the Sanford school system. Rather than take a break during the summer, she threw herself into the Summer Reading and Writing Workshop at the University of Southern Maine.

The lessons that Mills teaches are part of her own learning process in pursuit of a master’s degree in Literacy Education. She studies new techniques to supplement her years of classroom experience and then applies them in the practicum portion of the workshop. She’ll earn six credits toward her degree. Practicum experience is also a requirement for a Maine literary specialist license.

The younger students have just as much to gain. The workshop is open to kids in kindergarten to eighth grade. For some, English is a second language. Others haven’t found the right book to spark an interest in reading. Still others need practice matching letters to the sounds they represent. Every student in the program stands to benefit from extra instruction ahead of the regular school year.

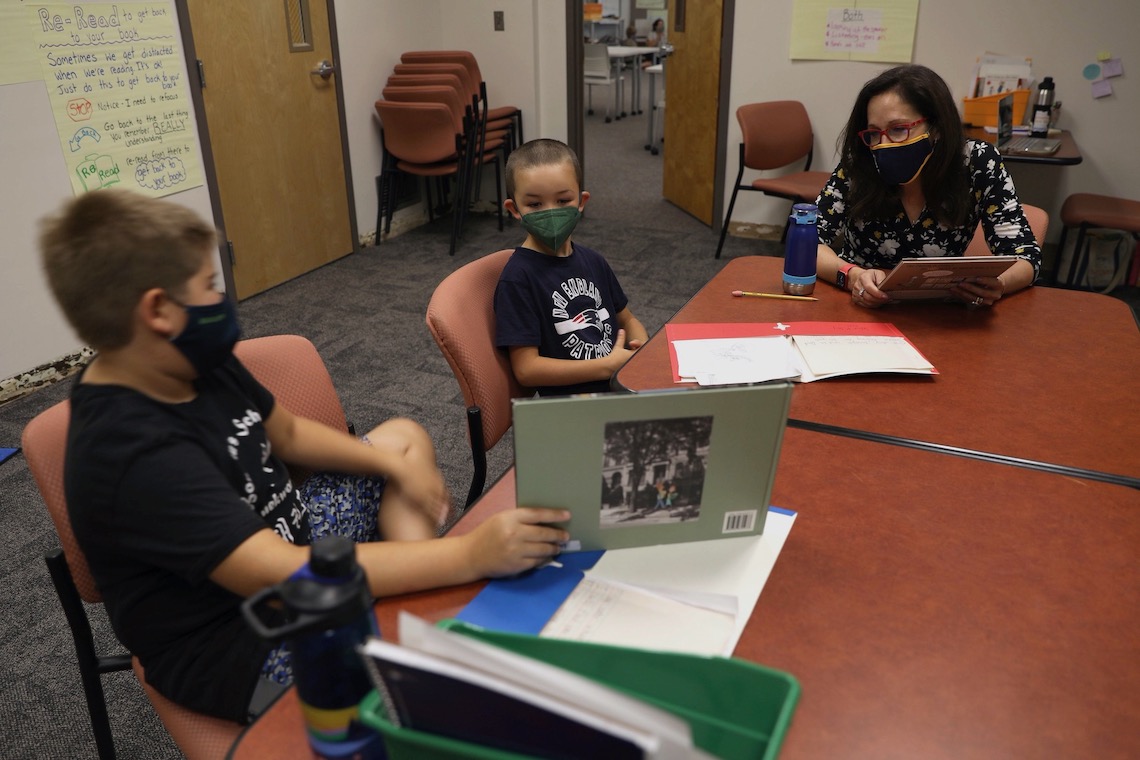

This year’s workshop includes eight teachers-in-training and 15 students. Teachers work with the same one or two students for the duration of the four-week program. The small group size ensures each student gets close, personalized attention.

“Having the opportunity to work with two students instead of 20 really gives us opportunities to get stronger at all the components of teaching reading and writing,” Mills said. “It’s more than just sitting and reading a book with students.”

The effort that Mills puts into book selection paid off with one of her students in particular. Eight-year-old Mia from Gorham loves to dance. She finally got hooked on reading when Mills introduced her to a book series about a dancing cat who is also named Mia. The personal connection made all the difference.

Mills found a different pathway to connect with 8-year-old Asher from Cumberland. He especially enjoys making new friends. Books are great conversation starters, as he learned when Mills and the other teachers would bring their students together each day for a group discussion. The books that Asher was most eager to share came from the Fly Guy series.

Having so many students together in the same room where they can socialize and learn from each other is a return to form for the workshop. The lessons were run entirely online through the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s so wonderful to have graduate students back in person, children back in person. And graduate students who are excited and, even though they had a choice, wanted to be in person,” said Dr. Melinda Butler, Department Chair of Literacy, Language, and Culture.

Butler shares the work of teaching and evaluating the graduate students with Leslie Lemieux, a longtime reading interventionist and coach in the Brunswick school system. Lemieux took the course as part of her own professional development. She returned in a leadership role which she’s held for nearly a decade.

“To see the parents dropping off (students), or the grandparents dropping off and picking up each day and make the face-to-face connection that we have been missing,” Lemieux said. “To have a conversation and see what they’re doing on the weekends, it’s just a reminder we are in service of our community.”

Some families, however, weren’t ready to return to in-person classes for reasons of health or transportation or convenience. A remote-synchronous option remained available for them. Five students and three teachers occupied the workshop’s virtual classroom on Zoom.

One of the online teachers was explaining the tricky pronunciation of the word “chaos” when President Jacqueline Edmondson joined the conversation via laptop computer. Her tour of the program on July 7 also included visits to the in-person classrooms at Bailey Hall. She spent time with each work group, often sitting on the floor to talk with kids at their own eye level.

“I love the University being a space where there are intergenerational programs and people from different ages coming together and this is one perfect example of that,” Edmondson said.

Those bonds between student and teacher, college and community, are rooted in history. Most of the children who take part in the reading workshop come from the Gorham area. In the 52 years since the program began, generations of students have built on the skills they learned to leave a lasting mark on their hometown.

The graduate students work hard to maintain that high standard. Preparations begin several weeks before the kids arrive on June 27. From that point until July 21, lessons ran daily from Monday to Thursday from 9:45 a.m. to 12:15 p.m. The days were longer for teachers. They clocked in at 8 a.m. to get their classrooms ready and stayed 15 minutes later for clean-up duty.

Instead of being worn down by the intensive workload, Mills draws energy from the trust she’s built with her students. “It’s amazing,” Mills said. “It’s amazing.”