A Political Science classroom would seem the obvious place for discussion about the mass protests across Iran. But at the University of Southern Maine, interest in the subject is also especially high in the Engineering Department, specifically the office of Professor Mehrdaad Ghorashi.

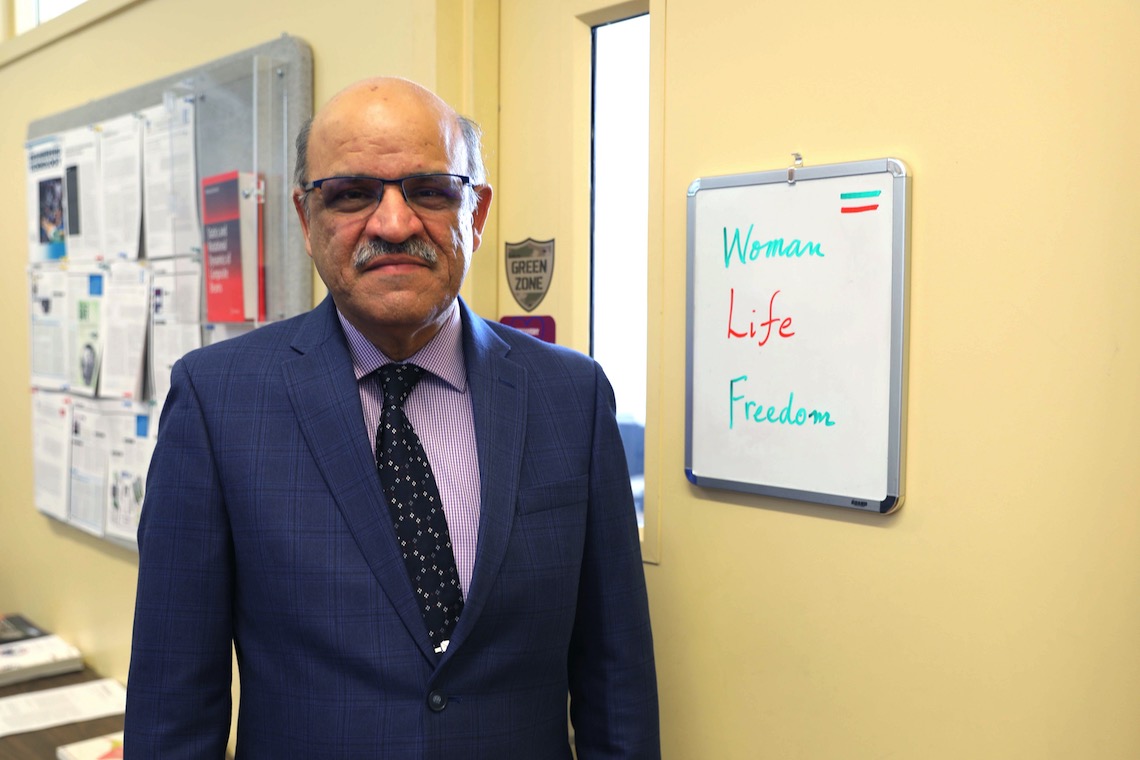

On the door to Ghorashi’s office at the John Mitchell Center in Gorham hangs a sign that reads “Woman, Life, Freedom.” It’s the rallying cry of the protesters in the country Ghorashi once called home.

“It is simply impossible to stay silent in a situation where a government kills its own citizens for demanding basic human rights,” Ghorashi said.

Ghorashi was born and raised in Iran’s capital city of Tehran. He was a teenager when the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini took control of the government.

Just before Ghorashi graduated high school, all colleges closed in 1980 and didn’t reopen for three years while the new leadership tried to restructure the educational system in accordance with its hardline views. This period also saw the first round of mass executions committed by the regime against its political dissidents.

Military service was mandatory and Ghorashi served six months during the Iran-Iraq War. When university education resumed in 1983, he gained admittance in the first nationwide entrance exam, leading to his discharge from the military. He entered Sharif University of Technology (SUT), eventually graduating in 1994 as the first Ph.D.-trained mechanical engineer in Iran. He also earned a master’s degree in Economic and Social Systems Engineering in 1998.

While still a graduate student, Ghorashi held management positions with Indamine Shock Absorber Manufacturing Company and Iran Vanet (Mazda) Car Manufacturing Company. He left the industrial sector upon completing his doctorate and went to work at SUT, first as an assistant professor and later as an associate professor.

The death of his mother in 1998 was a turning point. Soon after, he and his wife Marjaneh, decided to leave Iran to seek, as Ghorashi said, “a more stable and free place” to live and raise their two children, Mehrnaz and Ali.

That search led them to Ottawa, Canada, and Carleton University. Ghorashi taught a few courses and resumed his own education, resulting in a second Ph.D.

He moved again in 2009 to join the University of Southern Maine as the school’s first full-time mechanical engineering faculty member. One of the highlights of his tenure came in 2016 with the publication of his book, “Statics and Rotational Dynamics of Composite Beams.” In 2019, he was promoted from associate professor to full professor.

Ghorashi watched the news from Iran closely as tensions mounted over the last several months. It began last September with the death of Mahsa Amini following her arrest by the Guidance Patrol, also known as the morality police.

The now-defunct agency enforced the government-approved dress code by forcefully detaining alleged violators. The government has since adopted a new tactic to punish women who don’t adhere to the dress code by denying them services and closing their bank accounts.

Amini was accused of improperly wearing her head scarf. Her treatment in custody left her comatose. Three days later, she died. She was 22 years old. Outraged citizens took to the streets with women in the forefront. Many burned their head scarfs in protest.

“Iranians believe their 1979 revolution and their hopes for a better future have been stolen from them by those who seized power,” Ghorashi said. “Consequently, in the past four decades, their anger has built up and it was just waiting for a spark to explode.”

The Iranian government tried to end the protests with force. The United Nations Human Rights Council estimates hundreds of protesters have been killed, including tens of children. To learn the full extent of the bloodshed, the council launched a fact-finding mission last November.

Many more people have been hurt but they often avoid hospitals for fear that police will be waiting for them. Those who survive the street fighting only to be arrested still face the possibility of death by execution. They are often not allowed to choose their own lawyers to defend themselves in court.

Despite the danger, the protests have not only continued but spread to other countries where supporters held their own demonstrations. Some of those international allies have reported threats from Iran’s ruling regime. Its global intervention also includes providing aid to Russia for the war effort against Ukraine.

At the World Cup in Qatar, players on Iran’s national soccer team joined the resistance by refusing to sing the national anthem at their first game. They sang in subsequent games only after news agencies reported on threats against their family members back home.

Ghorashi has heard of similar intimidation tactics being used to stifle dissent on college campuses, such as his alma mater and former work place, SUT. He voiced his concerns about the conditions in Iran in a presentation to USM’s Faculty Senate. On November 4, 2022, the entire body released a resolution, which stated:

“In light of the current crisis in Iran and particularly the frequent attacks on university campuses by the regime forces, the University of Southern Maine Faculty Senate stands in solidarity with the academic community in Iran’s universities in their just cause for protecting their right of free speech and expression.”

Because of their ongoing nature, the protests are often fighting for limited news coverage against newer stories. Ghorashi is determined to raise awareness within his circle of influence in the hope that change will come, if enough voices demand it.

“The regime’s agents have clearly missed some history lessons,” Ghorashi said. “Killers have never succeeded in the long run.”

Click on the link to read a Q&A interview in which Ghorashi delves further into his thoughts and feelings about the conflict in Iran.