A series of collages on display at the Maine Jewish Museum uses layers of photographs, paint, and handwritten text to explore the layers of nationality, race, and religion that comprise the artist’s family history.

The artist behind the exhibition is Dr. Paula Gerstenblatt, an Associate Professor at the School of Social Work. Art has always been a vital component of her scholarship as a means to better understand the world. In creating Generational Layers, she turned that focus inward in the hope her art might provide answers from relatives who weren’t alive to speak for themselves.

“I started a dialogue with them,” Gerstenblatt said. “Things like, ‘What would you think of your Black grandchildren?’”

Work on the project began during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic when much of the country was housebound to keep from spreading the virus. Gerstenblatt cancelled a trip to visit the concentration camps in Poland. Her thoughts shifted to her grandparents who were fortunate to leave Europe before the Nazis came to power. Those memories soon found their way into her art.

Gerstenblatt’s grandparents were part of an early 20th century wave of Jewish migration to the United States. The two sides of her family settled in the South Beach section of Florida. Their new home wasn’t always welcoming. Kids from the neighborhood went to Hebrew school in groups to protect each other from antisemitic attacks.

Her family wrestled with their own prejudices, as well. Gerstenblatt’s two children, Rena and Jonathan, are biracial. Their identities are also shaped by the knowledge of their father’s upbringing as an African American under segregation. In some Jewish circles, they found themselves treated like outsiders.

Gerstenblatt saw her children’s experience as a continuation of the story that began with her grandparents. Between those generations, her family also endured the death of her sister in childhood. Her art was an outlet to make sense of it all, not just for herself, but for any family that lived through similar joys and tragedies.

“You don’t need to be Jewish to come in here and understand what grief is about or what it means to really examine your parents as people and then think of your own self,” Gerstenblatt said. “The intersection of antisemitism, racism, all that’s kind of mixed in. But isn’t that how life is, really?”

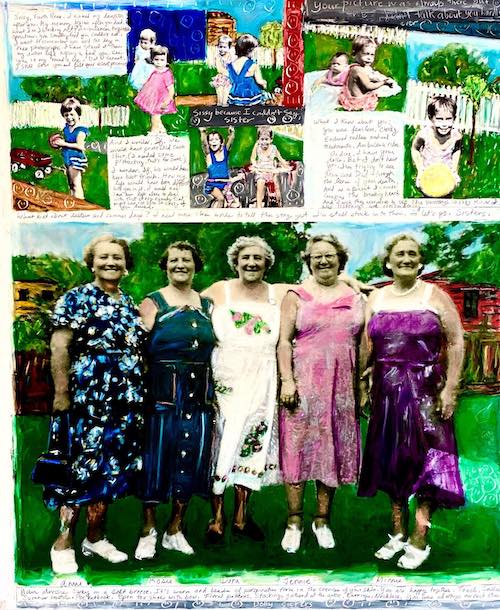

Gerstenblatt developed a narrative structure for her family’s journey across 17 canvases. She often spliced together photos that were taken decades and even centuries apart to create impossible reunions between relatives who never met. In one piece, her sister and daughter come face-to-face, building a bridge across the years that separate them.

The photos alone are compelling, but the accents that Gerstenblatt added heightened their impact. She used oil bars and pigments to draw the eye with surprising splashes of color. When more context was needed, she wrote her feelings into the spaces around the images.

Gerstenblatt describes her particular synthesis of subject and style as collage portraiture. She began experimenting with collage more generally in the 1970s. Her work reached a turning point in 2007 after taking a trip to Ghana with her son. She found a new way to focus her message by inserting him into her art. Generational Layers is the latest step in that evolution.

The Maine Jewish Museum gave Gerstenblatt a prime location for her art. The exhibition lines both sides of main corridor behind the front entrance on Congress Street in Portland. Many visitors who come for worship services or religious study will stop in their tracks to stare at an image that catches their attention.

The museum’s executive director, Dawn LaRochelle, has her favorite. It’s a group picture of five gray-haired women, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, smiling to be in each other’s company. They are pillars of their families, radiating strength and pride. LaRochelle sees echoes of them in her own family and she’s sure anyone else would have the same reaction, Jewish or not.

“Everyone is blown away by it. It’s very relatable. It’s very raw,” said LaRochelle about the full exhibition. “Everybody sees pieces of their story in Paula’s story. It’s been a wonderful bridge-builder as well as a means for self-reflection on people’s own lives.”

About 15,000 Jewish people live in Maine. The museum keeps the community connected as both a center for culture and a repository of history. Its ample gallery spaces are reserved years in advance. And the building itself is a work of art with architecture dating back 100 years and loving restored after a fire in 2020.

Gerstenblatt ’s involvement with the museum didn’t end when she handed over her art for display. The museum invited her back on October 6 to elaborate on one of the exhibition’s major themes — the historical tensions between the Jewish and Black communities. Fellow artist Daniel Minter and Dr. Leroy Rowe, Chair of the USM Dept. of History, joined her for the panel discussion.

Gerstenblatt returned to the museum on October 13 to coach aspiring artists through the basics of her collage techniques. They each brought copies of photos that held special meaning for them. Gerstenblatt helped them arrange and enhance the photos to tell their personal stories.

Andrea Levinsky signed up for the workshop on the museum’s website. She graduated from USM in 2022 with a master’s degree in Teacher Leadership. Her collage included photos of her family and scenes of her stay at Seeds of a Peace, a summer camp that brings together young people from different backgrounds to help them better understand each other.

“I’m really interested in cross-cultural collaboration,” Levinsky said. “The (Generational Layers) series being about connecting the Black community and the Jewish community was really interesting to me.”

The lessons that Gerstenblatt taught during the workshop would be familiar to her students at USM. She often incorporates art, like collage and mapmaking, into her Social Work curriculum. Students are still required to write essays and analyze policy. Art-based learning takes those hard statistics and puts them into emotional context.

In creating Generational Layers, Gerstenblatt modeled the same vulnerability that she asks of her students. The memories she stirred up weren’t always easy to face, but the exhibition wouldn’t be so affecting if it wasn’t so honest. Even though Gerstenblatt did all of the work to bring it life, she gives her family a share of the credit.

“In a way, with this, it really feels like they came through for me,” Gerstenblatt said. The exhibition opened on September 2 and it will remain on display the Maine Jewish Museum until October 27.