Aliens have landed. And ground zero was the Russell Hall stage at the University of Southern Maine campus in Gorham.

“The War of the Worlds” is the latest production by the Theatre Department. They first recorded the show as a radio play, then performed it at two live stage readings on March 7 and 8. By focusing on the spoken word, the actors found new ways to use their voices.

“There’s a difference in your voice when you’re smiling versus when you’re not,” said Nicole Bilodeau. “Learning to be expressive with your voice and coming across with all these emotions when people can’t see you is a really interesting skill that’s been really fun to learn.”

Bilodeau is a senior pursuing a double-major in Theatre and Media Studies. Her role as a radio broadcaster combines those two fields of study. The show is structured as a series of breaking news reports and interviews about an attack by Martian invaders.

Spaceships that zip between planets and laser guns are staples of science fiction. But those ideas were still new in 1898 when “The War of the Worlds” debuted in its original form, as a book written by H.G. Wells. Multiple adaptations would follow across various media, including a 2005 movie starring Tom Cruise.

The USM production used the same script that Orson Welles performed on the radio in 1938. The broadcast is infamous for convincing listeners that the events of the story were actually happening, although Welles may have exaggerated such claims for promotional purposes.

The trustworthiness of the media was a favorite topic for Welles. In 1941, he directed and starred in the movie “Citizen Kane” about a ruthless newspaper tycoon. “The War of the Worlds” delivers a similar critique beneath the veneer of an adventure story.

Sophie Urey is a Theatre major in her senior year. She plays a military officer. The audience is left to decide if her commanding tone conveys confidence or propaganda.

“That does unfortunately speak to the climate that we’re in right now where we will read something in the news and take that as fact, causing alarm and spreading panic, without doing research to back it up,” Urey said. “I think it’s an interesting thing that we’re bringing to the stage right now because it is unfortunately kind of topical.”

The show wouldn’t have been possible without the technology to properly dramatize Welles’ vision. A new recording studio with professional-grade equipment opened on campus at the start of the current semester. “The War of the Worlds” is the first Theatre Department production to make use of the studio.

“Of radio theatre, this is the most famous piece there is, so kind of a fun thing for us to do as our inaugural piece, and a really fun piece of history for students to engage with in 2024,” said the show’s director, Liz Carlson.

The cast began their recording sessions in January. Most of them were trained to incorporate body language into their acting. But the microphones were sensitive enough to pick up every shift in weight or rustle of clothing. They had to resist the urge to gesture as they spoke in order to get a clean reading.

Mike Lawrence loved the recording process. He played a farmer in his biggest scene and returned later in different supporting roles. It was like a flashback to childhood when he would entertain himself by trying to sound like Mickey Mouse and Kermit the Frog.

Now a sophomore in the Theatre program, Lawrence dreams of landing a job doing voice work for anime or video games. His exposure to the tools of that trade has only increased his enthusiasm.

“It’s been very amazing,” Lawrence said. “I’ve never really done much with full-fledged studio work and actual voice recordings. I’ve done a little bit of film in high school. But actually being able to work in a studio? It’s been really fun, it’s been very educational, and it actually ties in really well with a couple of my classes that I’m doing this semester.”

Before letting her cast cut loose on the mics, Carlson gave them homework. Their assignment was to study recordings from the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. Public speakers of that era commonly used the Transatlantic accent. The performers tried to sound more authentic by incorporating the accent’s inflections and cadences into their delivery.

“You break it down like it’s music,” Carlson said. “The metaphor that I use when I talk about it is you’re learning to notate the voice so that you can sing it.”

Sound effects were also essential to make the listener believe what they were hearing. The otherworldly sounds of the aliens were produced by popping bubble wrap and squeezing rubber balloons. A manual lawnmower convincingly mimicked the clang of heavy artillery.

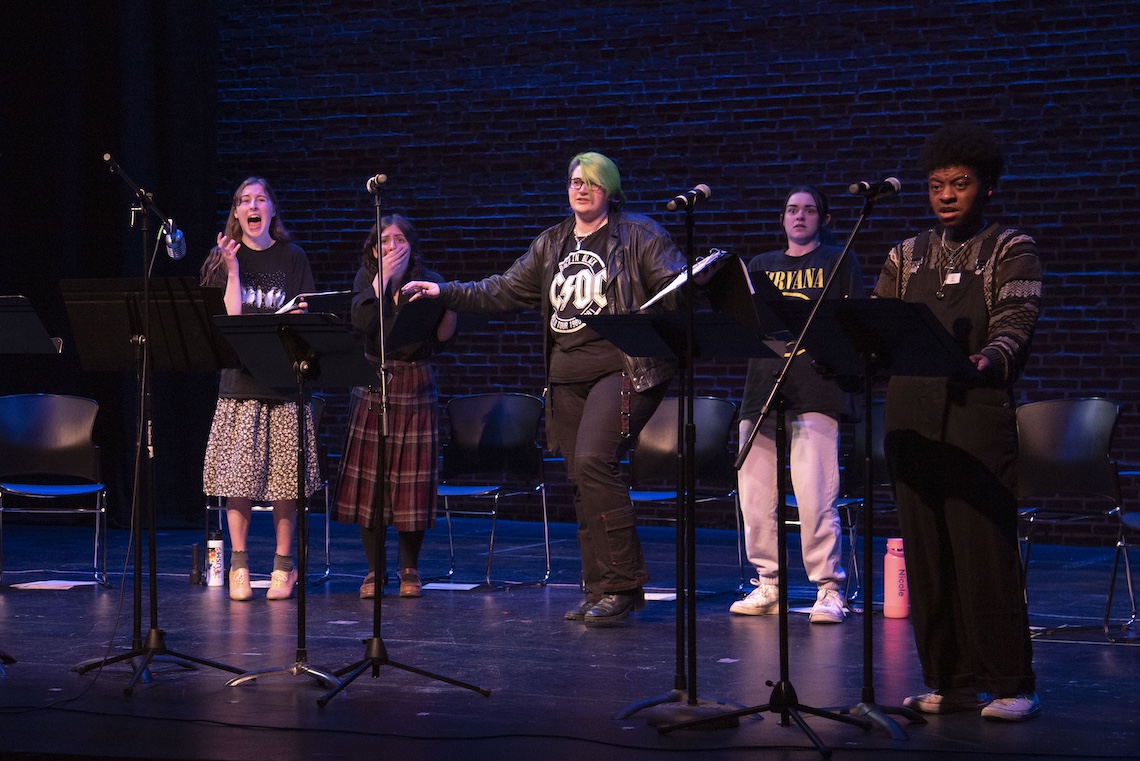

The two live stage readings allowed the audience to see how the crew pulled off its auditory trickery. A bank of microphones lined the front of the stage. Performers would step forward to say their lines and then recede into the background until they were needed again. The costumes evoked Depression-era fashion, topped by fedoras and pillbox hats.

The devotion to period detail continued even when the story took a break. The radio show was designed to pause for commercials. The production team filled the time with ads of their own creation to be read live. Instead of shilling for Ovaltine or Burma-Shave, they promoted upcoming shows by the Theatre Department.

“The War of the Worlds” completed its stage run, but the studio recording has yet to be heard publicly. The show will make its broadcast debut March 22 at 7 p.m. on campus radio station WMPG, which airs at 90.9 FM. The Theatre Department will host a listening party at the McGoldrick Center in Portland. Admission is free, but guests must RSVP online.

The ending of the show isn’t a secret. It’s been told and retold for more than a century. But Carlson has a theory about why “The War of the Worlds” still holds audiences in suspense.

“When things are shifting rapidly and massively, it is our ego that’s saying, ‘Of course, I am living in the end times. How could I not be living in the end times?’ That feels very present to us now, but also felt present then, and also will feel present again.”