It only took 150 years or so, but the University of Southern Maine finally caught the students who’d been sneaking notes behind their teachers’ backs at the Academy Building.

Gossipy scribblings, payment stubs, homework assignments. A gap in the wooden panels lining a stairway offered a convenient dumping ground for any scrap of paper that outlived its usefulness. Into the darkness it went, never to be seen again. At least, that was the intention until Lee Hoagland began his renovation project.

“It’s the best part of the job,” Hoagland said. “That’s the interesting thing, the discovery. When I went into that wall cavity, no one has been in there since the 1870s. It gets boarded up, and it’s in your building, and then no one looks in. So, I’m very aware when I’m looking in a place that hasn’t been opened in a hundred years or so.”

Hoagland is a contractor who specializes in restoring historic properties. The things he finds in the course of his work never cease to amaze him. Even within his considerable experience, the Academy Building was a treasure trove. He had a hunch it would turn out that way, based on his knowledge of the building.

Built on a hilltop in Gorham in 1806, the Academy Building predates the University. It originally served as a secondary school for children ages 10 to 17. Declining enrollment led to its closure in 1877. Soon after, construction began next door on a new school that would evolve decades later into USM. The Academy Building was eventually absorbed into the growing campus.

Old buildings need upkeep. A major renovation project at the Academy Building got started in the summer of 2022. The roof was reshingled, and the siding was whitewashed. But when attention turned to the eastern portico, the project hit a snag.

Some of the clapboard had deteriorated and needed replacing. When workers peeled back the surface layer, they found the damage went even deeper. Rainwater had penetrated the wall and ate away at the woodwork all the way down to the foundation. An expert’s help was needed, and Hoagland got the call.

Repairs were extensive. Hoagland rebuilt much of the wall, including the antique window frames. He shored up the second-story balcony and reinforced the wooden columns that supported it.

Since the Academy Building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Hoagland had to match the original design as closely as possible. He worked through snow and heat for more than a year to get every detail just right. The effort it demanded of him, even with modern tools, made Hoagland appreciate the original builders.

“It’s the most ambitious building I’ve ever worked on,” Hoagland said. “They really wanted to show, in 1803, that they were just as good as Europe. ‘We’re gonna make a school. And we’re not just gonna make any school, we’re gonna make a grand school on the top of the hill. With all this architecture, it’s gonna prove our sophistication.’”

Hoagland applied the same interest and care in his recovery of the paper scraps as he did to his carpentry. He eased the notes out of the crevices in the wall to minimize rips or flaking. They emerged by the dozens, maybe hundreds, enough to fill multiple cardboard boxes. Hoagland saved everything, not knowing which of his finds might be worthy of preservation and study.

That’s where Dr. Libby Bischof comes in. She wears many hats at the University as a history professor and executive director of the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education. It was in her role as University historian that the notes held special importance.

“Looking at these notes give us a real glimpse into the social history of what it was like to be a student in the Academy Building,” Bischof said.

The roughness of the notes is what makes them special. Many of them were never meant to be seen. They often reveal personal exchanges between friends in casual, unpolished language. Instead of the stiff, posed photographs seen in history books, these notes reveal real people whose thoughts and feelings are entirely familiar to modern sensibilities.

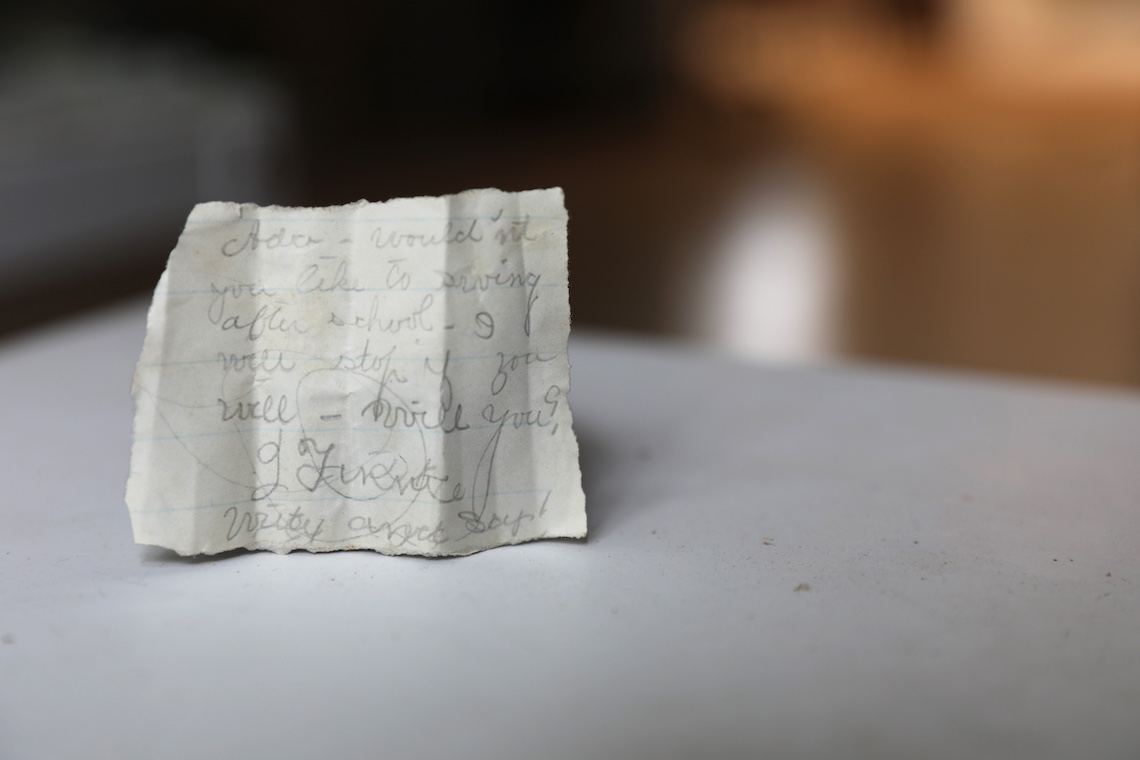

One of the notes offers a glimpse into 19th century social planning. Is it a get together between two friends or a rendezvous for lovebirds? The slang might change, but the air of middle school drama is instantly recognizable:

“Ada, would’nt (sic) you like to swing after school. I will stop if you will. Will you? Write and say!”

The note is remarkably well preserved, written on clean, white paper. Other notes haven’t aged nearly so well. Some are stained with water or dirt. And the cursive handwriting can be a challenge to decipher. For example, the next note may come across as either complimentary or catty, depending on your ability to make out the pivotal adjective in question:

“Bell Worcester is a (prissy or pretty?) girl.”

“It’s the same things that kids would be frustrated about now, that they might be texting to each other or Snapchatting to each other,” Bischof said.

And the rumor mill had more to say about Bell (or Belle, as it was alternately spelled). Hers is one of several names that appear repeatedly among Hoagland’s findings. If all of those Belles are the same person, perhaps the following note suggests “mischievous” might be yet another fitting adjective for her:

“We had a splendid time to (meeting?) last night, for Belle and I passed notes. We didn’t pass many though, for Mr. Lord was right behind us.”

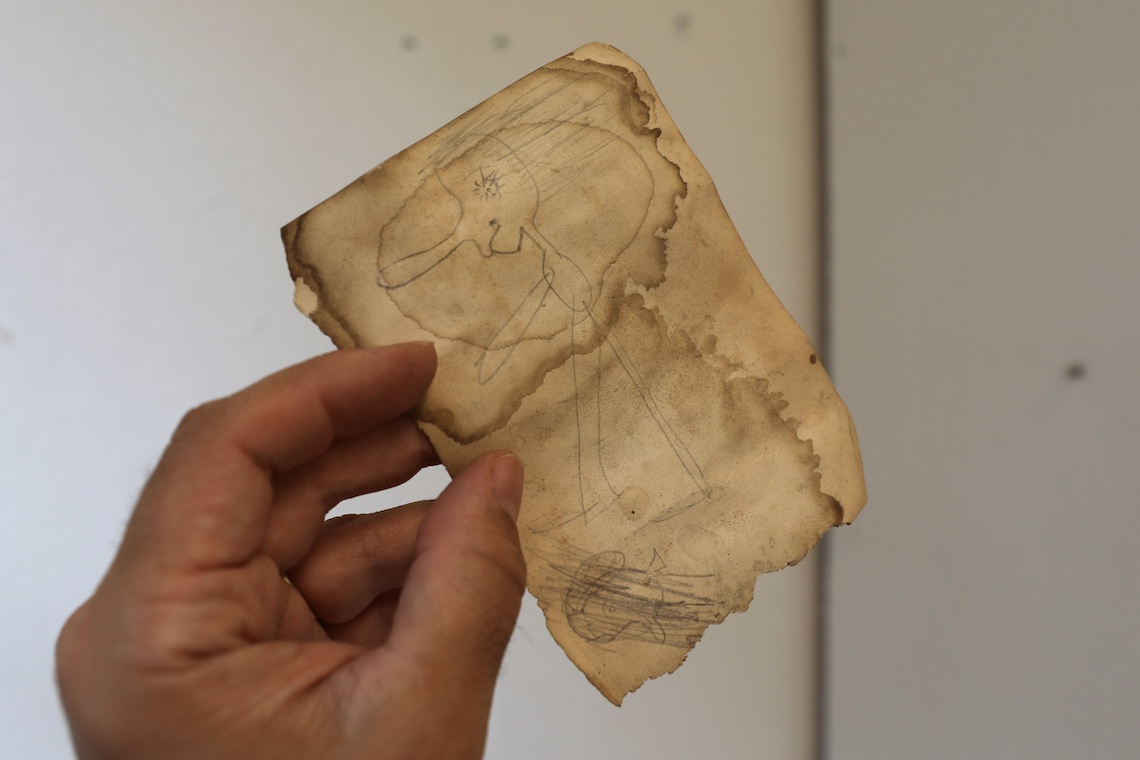

The cheekiness in some of the notes may account for their placement in the walls. Students may have worried that teachers wouldn’t approve of certain comments. The gap in the wall was a good place to dispose of the evidence, along with less than flattering drawings of the faculty.

“What really struck me was the Miss Stevens cartoon because it was so crude. Not in crude in a lewd way, but crude like a really bad sketch,” Bischof said. “And I could tell Miss Stevens had really large eyes because that’s the defining feature.”

Along with the usual student/teacher tensions, some notes also reflect more constructive interactions. The Mr. Lord who caught Belle passing notes is one of several teachers by that name who worked at the school. A course catalog from 1860 lists Laura E. Lord as permanent principal and preceptress. Her initials match the signature on a note that reads:

“Miss (Mary?) – We need not have an extra (talk?) this afternoon. I can hear your Latin some time tomorrow.”

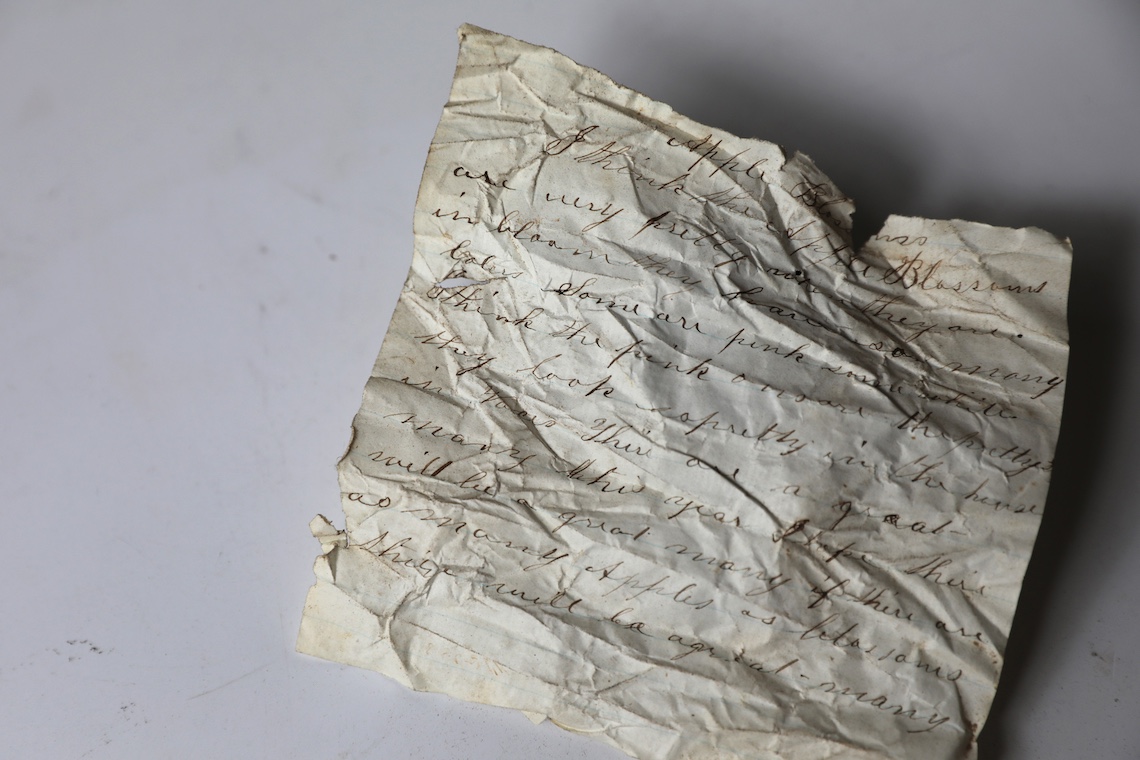

While that Latin assignment is lost, several other examples of classwork survive among the notes. There were math equations, verb conjugations, and long lists of words for spelling or vocabulary lessons. A crumpled page, once flattened, revealed a short essay on apple blossoms:

“I think that apple blossoms are very pretty when they are in bloom. They have so many colers (sic). Some are pink some white. I think the pink ones are the (prettiest). They look so pretty in the house in vases.”

The handwriting in the essay is more graceful than the hastily scrawled notes between friends. Casual messages also tended to be written in pencil, while ink was used on formal assignments for teachers. The decorative script written with fountain pens helps to date the notes.

Careful analysis of the paper beneath the writing can offer more clues about their provenance. Students used whatever scraps were available, including old envelopes and receipts. A promissory note that was found among the stash simplified the detective work by listing an exact date of October 5, 1873.

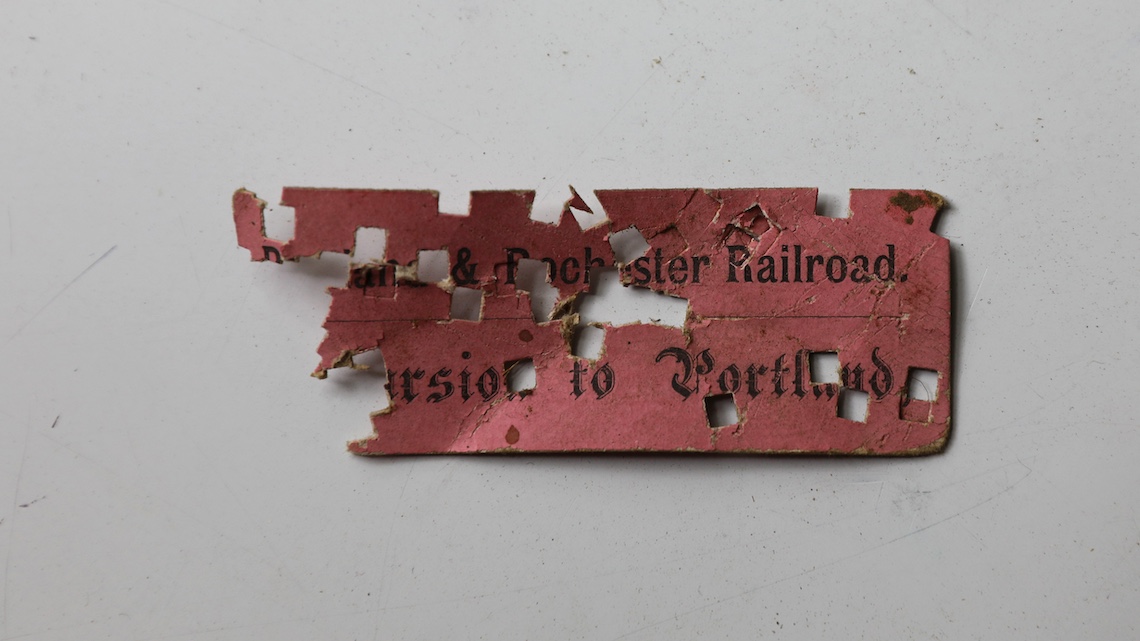

Several other items pulled from the wall speak to the rhythms of life in the mid-to-late 19th century. There is a train ticket for the Portland & Rochester Railroad, pages of newsprint, a 3-cent postage stamp, and an empty spool that served no further purpose once its thread ran out.

Hoagland boxed up everything he found before completing his renovations at the Academy Building. The final touches were left to other workers who rebuilt the stonework of the front steps and reseeded the grass that was torn up by all the construction equipment.

The last of the scaffolding and fencing came down shortly after commencement in May. When the full student body returns to campus for the start of the fall semester, they’ll get a clear look at the fully restored Academy Building for the first time in nearly two years.

“People don’t want to tear down beautiful buildings, and people don’t want to tear down historic, important buildings. So how do you prove that they’re beautiful and historic?” Hoagland asked. “Well, you find history, and you keep them beautiful.”

The Academy Building is currently occupied by the Department of Art, chaired by associate professor Hannah Barnes. As Hoagland filled box after box with notes, he’d drop them off in Barnes’ office for safekeeping. She still has them, while arrangements are made for a more permanent home.

Bischof wants to see the notes end up at the Special Collections wing of the University library. The archivists there are experts at preserving old documents. Through their efforts, the notes could become a valuable resource for research into student life in the 19th century.

“I think generations of USM students are gonna really enjoy seeing what their counterparts from hundreds of years ago did,” Bischof said.