A graduate student at the University of Southern Maine, Alexandra Hood needed some research experience.

Although she had a background in the arts, she was working on her master’s degree in Counselor Education for Clinical Mental Health and daydreaming about a new career path that could lead her in a more analytical direction — to a Ph.D and teaching.

“But I don’t have the skills on my resume,” Hood said. “I was like, I want to try it out, get my feet wet.”

Elsewhere in Portland, Birth Roots needed help with research.

A small, nearly 20-year-old nonprofit focused on support for early parenthood, Birth Roots was hugely in demand, growing from 300 to 400 families a year pre-pandemic to more than 700 last year. It’s on track to serve close to 900 families this year. The problem: Birth Roots needed much more funding to keep up with that demand, but it didn’t have the tools to explain to potential funders how and why its mission was so vital. Nor did it have a great way to evaluate the impact of its programs.

“We knew that was an important next step, to actually be able to create the data that would be important for telling our story to funders, telling our story to our board of directors — even just troubleshooting our programming to make sure it’s having the intended impact,” said Executive Director Kate McCarthy.

Enter the Data Innovation Project (DIP) and its Applied Research Fellowship Program.

Matched with each other last year, Hood got training, support, a stipend, and scholarship to help Birth Roots, while Birth Roots got an enthusiastic graduate student dedicated to meeting its needs.

By the end of the school year, Hood had the research experience she’d been dreaming of, and Birth Roots had the tailored client survey and research-guided mission documents it desperately needed — documents that helped Birth Roots secure its first-ever $10,000 grant from the Maine Community Foundation.

“The grant reviewer, when she called me to do an initial call to ask questions about our proposal, said this (application) was really well written, it was very well laid out,” McCarthy said. “And that is absolutely related to the DIP program and Alexandra’s work.”

Part of the Catherine Cutler Institute at USM’s Muskie School of Public Service, DIP was established in 2016 with funding from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. DIP helps Maine nonprofits, community groups, and mission-driven organizations with data, research, and evaluation — analytics that are essential for their growth but that take skills and knowledge they may not have. Typically, organizations sign up for one of DIP’s free data clinics or hire the program to provide expertise.

In 2017, DIP began offering a new way to help: the Applied Research Fellowship Program. USM grad student-fellows get training and paid experience while organizations get their own training and free assistance with specific research goals.

“In under-resourced organizations — or even highly resourced organizations — it’s the kind of work that falls to the wayside,” said Elora Way, Research Associate for DIP.

The fellowship has proven popular with both sides. Each year, 10 to 15 grad students and 20 to 25 organizations apply for five slots. Some organizations apply year after year hoping to get in.

When the fellowship began, most student applicants were working on a master’s degree in Public Health or Policy, Planning, and Management. Today, fellows come from a variety of programs, including Social Work, Education, and Leadership. Because DIP provides training, support, and regular check-ins with a supervisor, students don’t need to have a background in analytics.

“Students who are good at taking initiative and are good at critical thinking, they’re the people we can support through this process because we do our own professional development with them,” Way said.

That sounded great to Hood, who had the drive but needed the experience.

“I needed work and I wanted to do something that made sense for me and gave me skills. And I also loved the fact I would be able to work with a community organization, which is really important to me and my values and my own personal history,” Hood said. “I was thrilled to be accepted.”

McCarthy was thrilled to learn that Birth Roots had been accepted, too. The nonprofit applied to the program previously, but it wasn’t ready. This time, it had clear, achievable goals that a fellow could help with

“I could not say more wonderful things about (Hood),” McCarthy said. “She showed up with all the excitement and enthusiasm you would hope for when bringing in a new person. She’s not a parent herself and yet was able to fully understand what it was we’re trying to do at Birth Roots.”

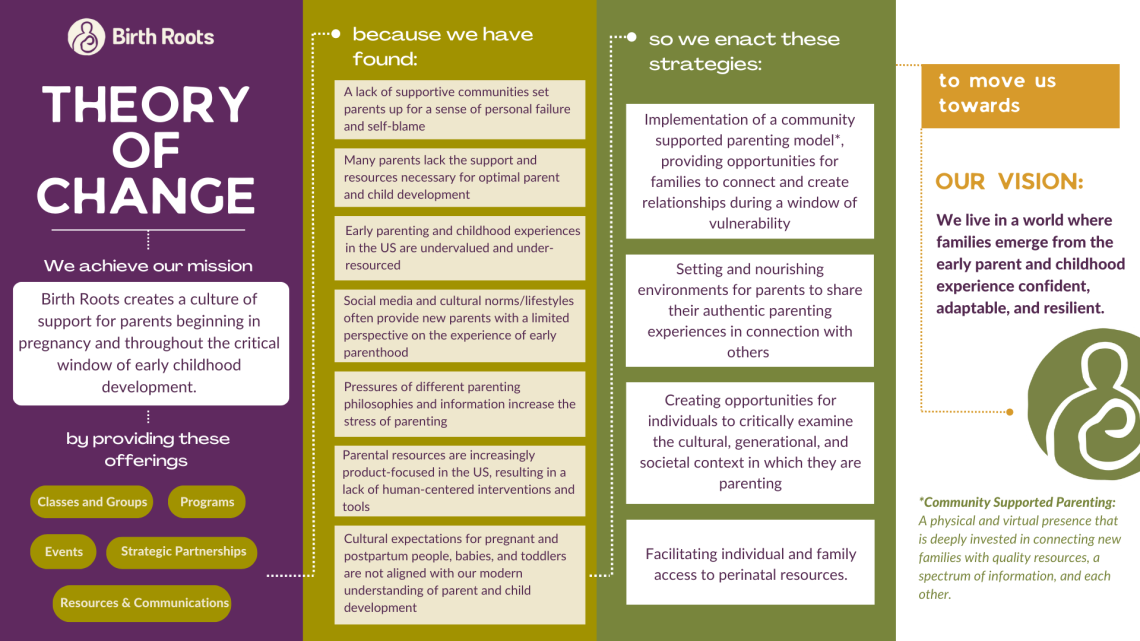

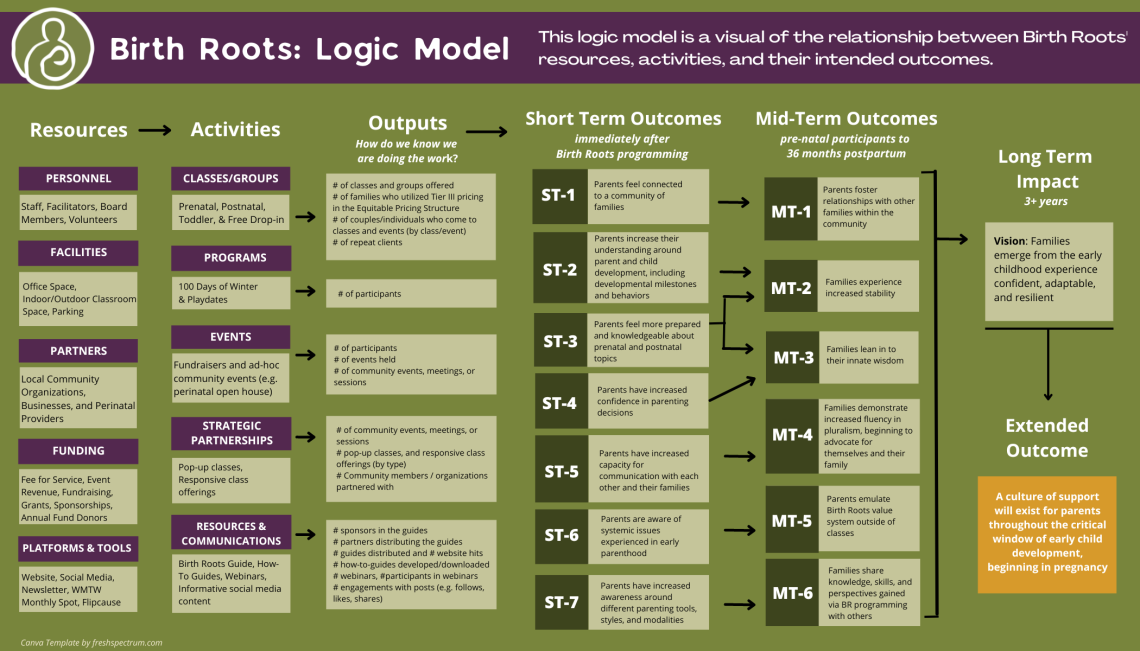

Hood spent about nine months putting together intricate “Theory of Change” and “Logic Model” documents that outline how and why Birth Roots’ work is so vital to the community. She also created client evaluations that the organization can use to gauge how it’s doing.

Because time was limited — fellows work about 10 hours a week for two semesters — it wasn’t feasible for everything on Birth Roots’ original to-do list to get done. That’s not unusual.

“For the student, I think it’s an incredible opportunity for them to interface with an actual community organization and learn what it’s like to do this work in the field,” said Rachel Gallo, Research Associate and Hood’s supervisor in the program. “What you learn in the classroom is never how it works in the real world. There’s never enough time or money or resources. Things break. Timelines get shifted. I think for the students it really helps them learn some skills of how to adjust and be flexible in the real world and what it takes to get the work done.”

Hood’s work pleased Gallo, who happens to be co-chair of Birth Roots’ board of directors. It also delighted McCarthy.

“It was better than even anticipated,” she said.

The documents turned out so stunning, both visually and for the information they conveyed, that Birth Roots’ leaders framed them and hung them on the wall.

Hood’s work wasn’t just a showpiece. With her documents as a guide, the organization was able to secure a $10,000 grant from the Maine Community Foundation.

“That’s really big for a small organization,” Gallo said.

That money will be used to help Birth Roots expand its programs to underserved populations, including BIPOC families, single-parent families, and LGBTQ families. The organization will also create a sliding-scale fee structure so more families can join.

“I told Alexandra I completely credit her and this work we did together,” McCarthy said.

DIP is looking at an expansion of its own. It is considering the feasibility of working with the University of Maine to bring the Fellowship to the Orono area.