Campus Police officers at the University of Southern Maine have a demanding job. But the latest addition to their workload is proving to be a real “snap.”

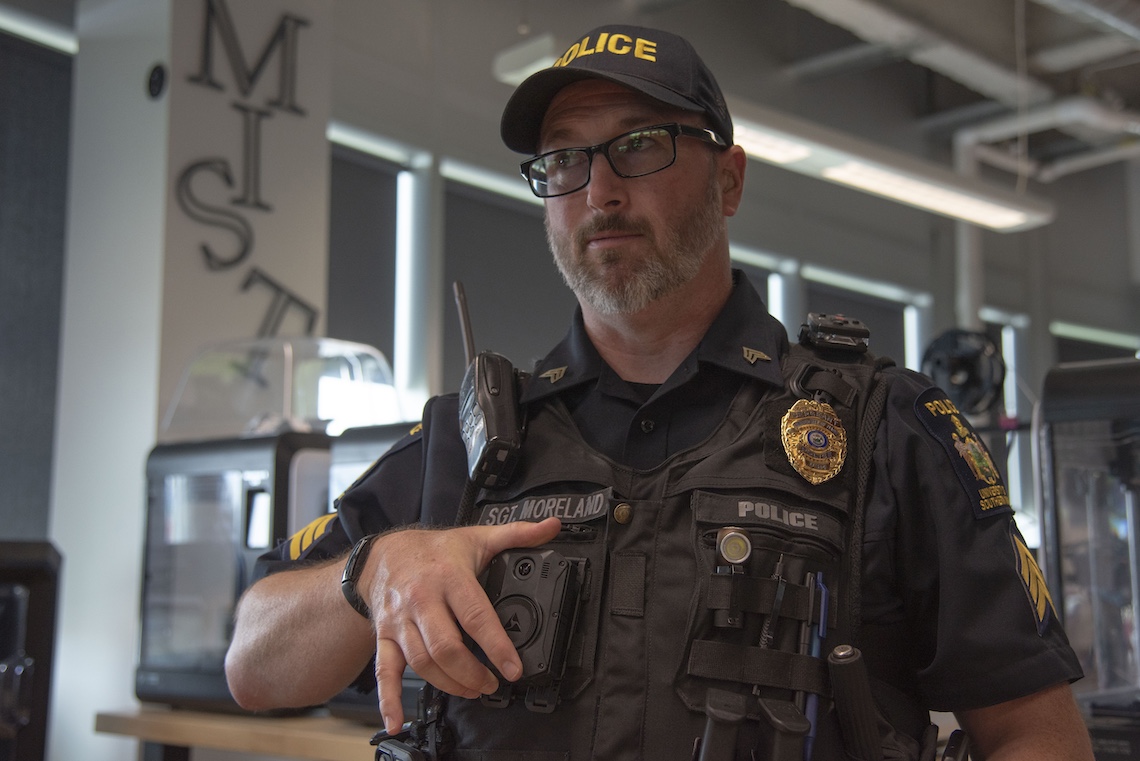

That’s the sound their new body-worn cameras make as they lock into place. The locking device was not included with the camera purchase. The department was considering its options when a solution occurred to Sgt. Benjamin Moreland in the course of his duties.

“I happened to get called up here one night to the fifth floor of the Science Building to unlock a room for a student,” Moreland said. “The elevator doors opened directly opposite of the MIST Lab. I looked in there, and I was pretty amazed. I’m only familiar with the idea of what 3D printing is. I’ve never actually seen it or been a part of it.”

Moreland soon got very familiar with the process. The MIST Lab (formally known as the Maker Innovation Studio) is an experiential learning classroom for designing and fabricating working prototypes of everything from toys to medical equipment. What about a locking device for a body cam? All that Moreland had to do was fill out a request form.

The body cams’ manufacturer designed them to fit over a regular shirt. But several officers at USM also wear a second layer of clothing. The Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE) vest is covered in straps and pockets to carry all the gear an officer might need. The body cams require a special attachment to account for the extra fabric.

That challenge landed on the desk of Drew Sfirri, the MIST Lab’s lead technician and special projects manager. He developed two designs. For the first one, the body cam would slide into a seating that was shaped like a small bucket.

A few problems with the bucket-design soon became apparent. If it was hit hard enough, the body cam would pop out. Sfirri tried to counter that flaw with a tighter fit until officers had a hard time pulling the two pieces apart. And the longer the cameras remain stuck, the more their batteries run down when they should be charging up instead.

“You don’t want to add challenging steps because that’s how you get people to not use it,” Sfirri said. “I’m very much in support of people using body cams, so I wanted to make it as easy for these guys as possible.”

The second design was more streamlined. Sfirri came up with a simple, flat bracket in the shape of the letter H. The bracket anchors onto the vest. Then a prong on the back of the body cam fits into a slot at the bracket’s center. A slight twist locks it down. Not only was the H-design easier to use, it proved to be more stable.

“With the prototypes, we actually gave people the opportunity to try them on, wear them for a couple hours, just to feel how they were in their regular workday,” Moreland said. “They had the opportunity to sit in the car and put a seatbelt across, see how far it sticks out, whether that’s an issue for normal function. This is the one that people picked.”

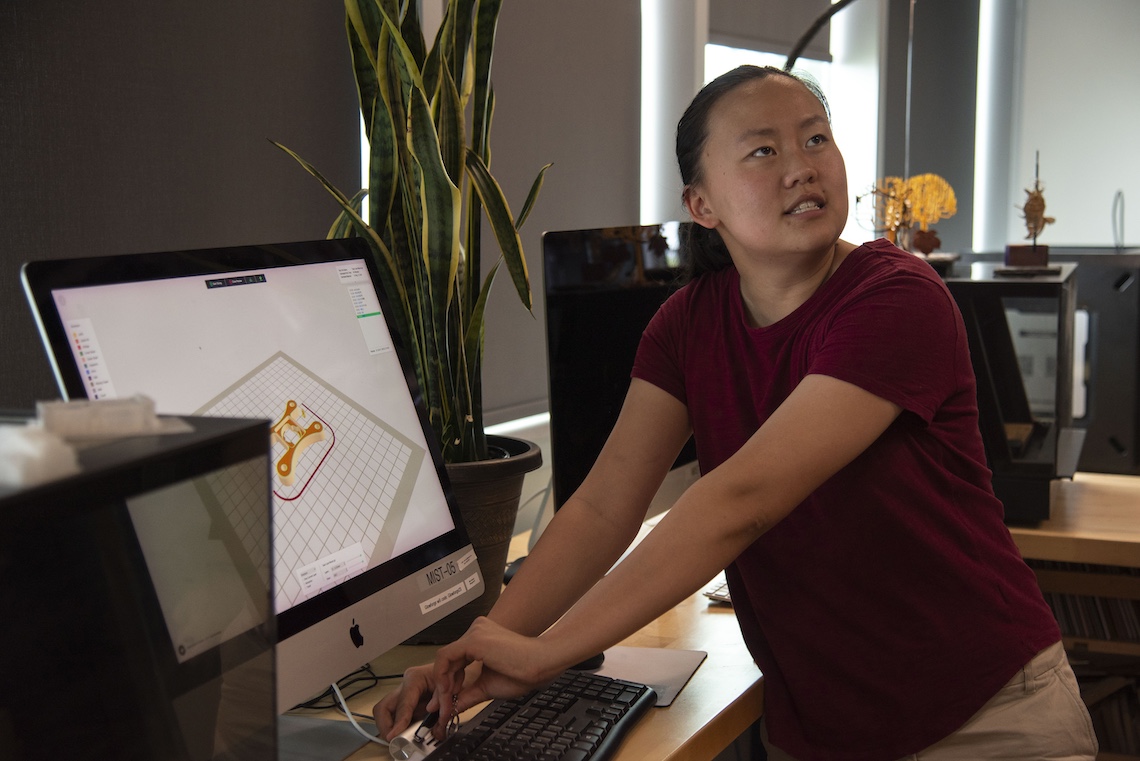

Sfirri first created his designs digitally, working out the details on his computer. When he was ready to turn his ideas into reality, he transferred the data into a 3D printer via flash drive.

The printer resembles a large microwave oven, both in size and general appearance. A window on the front door reveals what is happening on the inside, while a display screen counts down to completion.

A push of the start button sends the print head into motion. It continually traces the shape of the desired object, releasing small amounts of liquid plastic that solidify almost immediately. Around and around it goes until the object is fully formed. The process takes about 45 minutes for a single bracket.

Out of a huge selection of plastics, Sfirri chose to make the brackets out of NylonX, which contains carbon fibers as a strengthening agent. The resulting bracket is deceptively durable despite its slim dimensions of four inches long, three inches wide, and a quarter inch thick.

The raw plastic goes into the printer as a thread-like filament. A full spool of NylonX weighs just over one pound. That was enough to make 12 brackets with extra plastic to spare.

Before putting their trust in this new piece of equipment, officers got to see all the thought and care that goes into the 3D printing process. The MIST Lab’s director, Dr. So Young Han, welcomed a delegation from Campus Police for a tour on June 27. Her guests included Moreland and several fellow officers, along with police chief Gráinne Perkins.

“For our officers, collaborating with departments like the MIST Lab enhances their problem-solving skills and broadens their perspectives by exposing them to different fields and expertise,” Perkins said. “It also really fosters a sense of community and teamwork within the University.”

Now that the cameras are in full working order, Campus Police are almost ready to use them. Officers have been getting familiar with their capabilities all summer, building up to a full rollout in the fall semester.

The work to reach this point began years ago. The University convened a task force to analyze campus policing practices as part of a national movement that resulted from the death of George Floyd in 2020. Floyd, a Black man, died after being beaten by a white Minneapolis Police officer.

The task force recommended outfitting Campus Police with body cams. The video would serve as an impartial record of officer interactions. Deputy Chief Tim Farwell secured multiple grants from the U.S. Department of Justice to cover the brunt of costs for eight cameras.

The vest attachments were an unforeseen expense that came out of the department’s budget. Commercially produced models sell for more than $100 each. The MIST Lab made all 12 brackets for only the $58 it cost to buy a spool of NylonX. With almost half the spool remaining after the initial batch, that money will stretch even further.

After such a successful collaboration, the Campus Police are looking at other opportunities to work with the MIST Lab. The idea was floated to use the lab’s industrial sewing machines to embroider officers’ hats. The lab also works with metal, which opens the possibility of minting commemorative challenge coins.

And more vest attachments are always a possibility. All of Sfirri’s designs remain on file so he can easily make replacements for any units that break or wear out. He was there when the officers toured the MIST Lab, and getting to meet the people who benefit from his work left an impression.

“I sometimes do take for granted the ability to take an idea from somebody’s head and turn it into a final product that they can touch and hold and manipulate,” Sfirri said. “I find a lot to be rewarding in this work, in helping out.”