November 2022

Dear USM Community,

As members of the Convocation Committee, we would like to invite you to join us in this year’s Gloria S. Duclos Convocation, “The Rivers We Belong To: Grounding Indigenous Presence and Sovereignty.” For the remainder of the 2021-2022 academic year, and into the 2022-2023 academic year, we will be hosting and offering a variety of programming (both virtual and in-person) related to the convocation theme. Lectures, webinars, field trips, professional development workshops, panel discussions, craft demonstrations and common reads are just some of the events to look forward to in the coming months.

Traditional Indigenous knowledge systems and lifeways are inherently tethered to the land they belong to and build off of this fundamental truth of belonging to the land to create sustainable, mutually beneficial community-based relationships with the land and its inhabitants. Tribes of the Wabanaki confederacy represent thousands of years of stewardship and honoring of this land, offering compelling counterarguments to the role of the land in our society and meaningful insight into symbiotic ecological relationships with deeper cultural significance. Traditional, place-based knowledge centers the responsibility of ecological stewardship and underlines the need for the perpetuity of a culture that nurtures that framework of thinking. Our hope is that by centering the topic of this year’s convocation around Indigenous presence, sovereignty, and resilience we can highlight the incredible work being done in these spaces by Indigenous scholars, activists, artists, and community members and spur meaningful conversation and action amongst the broader USM community.

As we enter into this conversation together as a community, we ask that you please take a moment to reflect on the rivers or watersheds you grew up with as a child, and the ones nearby you now. Which people(s) belong to these waters? What has the river of time changed about this age-old relationship? What does your own relationship to these waters look like and feel like? What can we—each and every one of us—do now to acknowledge, repair, and support the presence and sovereignty of the people(s) indigenous to this place? This is the rewarding work that lies ahead.

This year’s Convocation is an extension of the 2020-2021 Duclos Convocation theme: “Indigenous Peoples: Recognizing and Repairing Harms of Colonized Systems.” We are grateful to all who participated last year and for the fruitful conversations that were started and the work facilitated by last year’s committee and community, including the essay project: “Indigenous Perspectives: Honoring Native Voices in Maine and Beyond,” which you can visit here.

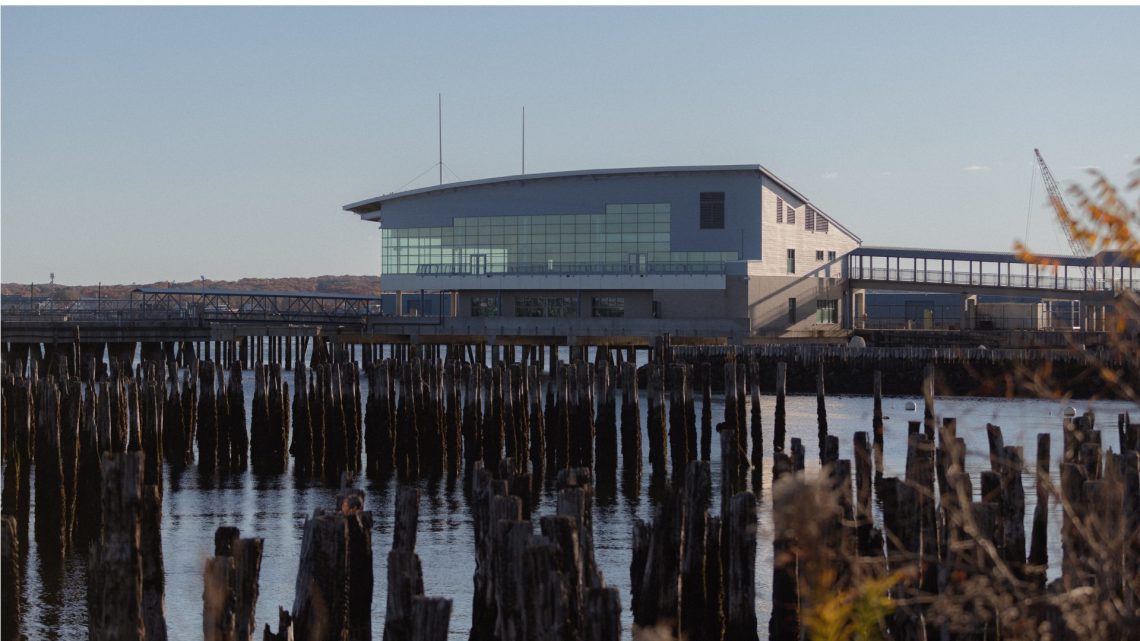

We would like to begin our work together in community this year by inviting you to read the poem “Song for Machigonne,” by poet, artist, educator, and USM Alumna Mihku Paul (Maliseet). The poem, first published in the 2013 anthology, Port City Poems: Contemporary Poets Celebrate Portland, Maine, is accompanied by a series of contemporary photographs of landscapes and landmarks mentioned in the poem, taken by Jared Lank (Mi’kmaq).

When asked how this poem came to be written, Mihku recalled:

In 2012 I happened to be on a panel with Colin Sargent and Donna Loring at a bookstore in Damariscotta. Colin asked me afterward if I would submit something to an anthology coming out that was being edited by then-Portland Poet Laureate, Marcia Brown. I agreed to do it, and asked him how much time I had to write something. “The deadline is in two days,” he said without batting an eye. Then he asked what I might write about, being a Waponaki woman born and raised in Maine, with obvious strong opinions. “Well,” I said, “I have always been troubled by the kiosk that stood for years and years in front of the old Jordan’s Meats hot dog factory.” I added that I was well aware a major battle had taken place there, as part of the very colorful and unsettled history of our city.

When I got home I set to work at my computer, reading up on the history of Portland and that lit a fire in my belly. The more I read, the more I realized I could not simply write about Fort Loyal, because that battle was part of a much larger story of conflict and displacement for Maine’s Indigenous peoples. As I learned about the seven wars that were fought in this region, I discovered that Portland actually had three different names, with Portland the final permanent name of our city by the sea. These three names are woven into the evolution of Portland as it

changed from a Waponaki seasonal gathering place to a colonial settlement focused on marine commerce and resource extraction.

I had never been given the opportunity to learn this history when I was growing up in Old Town. In fact, we were taught the absurd fallacy of the pilgrims around Thanksgiving and over the winter we were taught the westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. I knew more history of the western tribes and the Indian Wars than about New England tribal history and colonial conflict.

I was influenced somewhat by various oratory segments I had read, where statements of tribal leaders in this region had been recorded, and decided to try and capture some of that style and directness and lean language as I moved through the historical timeline. My goal was to ensure that while facts entered the poem, that the piece kept its own sense of witness and progression through periods of conflict and name change. This was to be a poem strictly from the Indigenous perspective but in a style that echoed those voices from the period. I felt myself pulled into the story in a way I had not experienced before, and once the poem felt complete enough, but also as lean as I could make it, I stopped. Sixty-six lines.

The passion I felt creating this poem gave me a level of focus I seldom experience when I am working. “Song for Machigonne” was no longer my poem; it had brought itself to life as a truth that demanded to be told. I felt I was simply the instrument that organized the language with a nod to aesthetic tradition and stylistic choices. History came alive for me, and I realized, someplace between being an eight year old mixed blood Waponaki girl attending white public school and a recent graduate student of writing at USM, this story entered the public space.

The story of the Fort Loyal battle and Portland’s three names, and the conflicts and the seven wars was all there in the historical record. It just needed to be told in a new, more accessible way. As I built the poem, I saw the sea-run fish being hauled from the rivers and loaded into ships. I heard the giant white pines fall, and heard the shouts of settlers and the sounds of battle. My awareness was altered because the history of this place entered my imagination in a powerful way. We all have an ability to inhabit the history of place, and find a deeper understanding of the human condition through learning about the patterns of colonization and exploitation that shape the land we call home. It can shift our perspective; something I hope “Song for Machigonne” will continue to do.

Song for Machigonne

Mihku Paul

Machigonne, your truest name before the French and English came to

raid the land of her tallest trees and pull the fish from her blue knee.

The fur they took in trade for pots and drink and rusty blades, could not sate

their endless hunger or abate their supernatural greed.

Oh, Machigonne, your name is dust.

You have begun to bleed.

Casco, now, is how they call the great neck as the mighty trees fall.

Land divided among men is stolen once again.

Waymouth kidnaps five of us before Gorges and John Mason arrive

to claim the eastern lands, and now we die and die.

Treaties cannot last when traders block the fish from moving past,

cows trample our corn, yet you say we are a thorn in your side.

You are the ones who cannot abide by your own laws.

When we fight, we have just cause to grieve for Machigonne

and those who now walk beyond this world.

French or English, we must choose or so you say, if not to

lose the land we hold most dear.

We come away only to starve anew and now our hearts are hard.

In spring of 1690, we gathered with Castine, our anger

risen like the streams you choked with nets to starve our kin.

We followed one trusted chief whose child the Baron sought to keep.

Madockawando leads the men and killing will begin.

Just for today we are many and shall break our anger on your flesh,

burn your walls to nothingness.

Four hundred fighting men and more, with French to

batter down the door, we come to Machigonne to prove

Fort Loyal cannot stand against our warring hand.

An English is a worse brigand than any Frenchman, so they tell us

when we fight and burn your forts down in the night.

We are not the ones you trusted to survive, white flag waved before your eyes.

That was Burneiffe, in charge of keeping order and giving quarter.

Trust is almost always wise but not to trust your English lies.

Thus you learn the bitter price you pay for our forgiveness.

Six wars were fought here, laying claim to land that

many tried to tame until we finally surrendered,

Penobscots, Micmacs, Malecite, Abenaki with little left

you had not plundered from our dawnland home.

The “Beaver Wars” were fought for pelts,

King Philip’s War, abuse of trade, and Squando’s child,

drowned just to see if he could swim, like some wild river otter.

Then scalp hunters seeking bounty in the south returned to seek us out.

King William’s War, fought for land, Fort William Henry could not stand against

Abenaki and French, who drove the English from the lower Kennebec.

In 1701 Queen Anne’s War came to our shores, when,

once again French and English wanted more and more and more.

Greedy bullets, dripping blades, smoking battlements laid waste and always

we must take a side, knowing we can no longer hide from settlers

thick as leaves on trees, coveting everything they see.

Dummer’s War for William Dummer, who sent Colonel Westbrook to

burn our homes and fields and starve us out.

Norridgewock fell, one hundred dead.

Pigwacket too, and if you wore the other shoe it would be dipped in red.

At last your war with France burned high, for seven years, we had

nothing left to lose when forced to choose between

the evils that befell our people.

Three in four of us was dead, gone to the wind.

Finally you said the line was drawn in seventeen and fifty-nine,

those words you give to white man’s time.

Our demise, battle victorious, so-called history and glory,

we fought for land paid in blood and bone.

Machigonne, just one of many, first become Casco, then Old Falmouth,

years wore on and Portland Maine became the name.

The massacre you blame us for is but the story of your shame,

those sins for which you must atone.

Machigonne was not your own.

We look forward to being in community with you all in the upcoming months.

Warmly,

The Members of the 2021-2023 Gloria S. Duclos Convocation Committee

Libby Bischof (Co-Chair)

Nadine Bravo

David Everson

Sarah Grinder (Co-Chair)

Sarah Holmes

Kelly Hrenko

Mihku Paul

Lydia Savage

Michael Shaughnessy

Robin Talbot

Ashlyn Tomer

Aaron Witham