MSFC Newsletter Archive

Don’t forget to pre-register for the season to stay in the loop!

Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter

Issue 1

October 10th, 2025

Hello Film Makers, and happy Friday!

This year, we are sending out a bi-weekly newsletter to our team coaches/competitors with news updates for the challenge, timeline suggestions, and resources for your films.

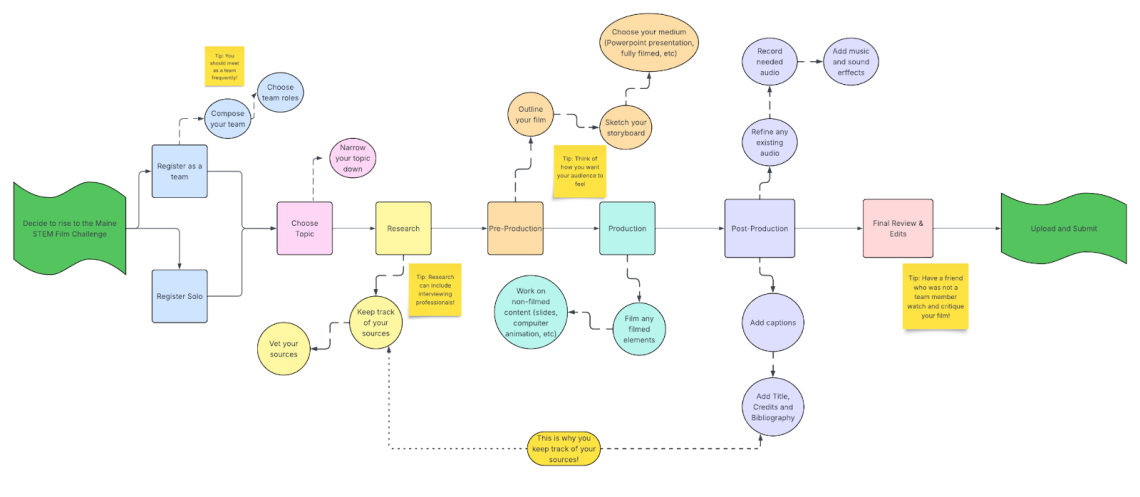

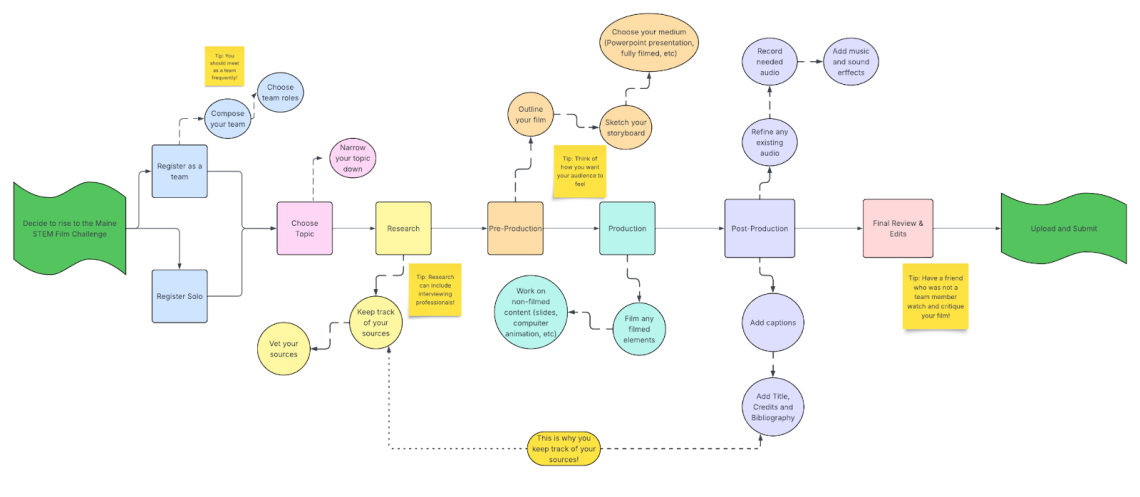

To see this timeline larger, click here! Feel free to use this timeline for yourself or with your team.

Today is October 10th, which means you have 20 weeks until submissions close (though, we do recommend that you give yourself plenty of time before the deadline to submit, just in case of any errors via Murphy’s Law!) These newsletters will be based on steps of the process, not exact dates you should have these steps done by. Everyone works differently, and with our extended season, people are welcome to join the competition at any point before submissions are closed.

This week, we’ll discuss how to select the topic for your film. We are always blown away by the wide range of topics that people choose to make their films about– we often learn a lot about some really cool STEM happenings just by judging them. However, for some, an unlimited range of topics could be overwhelming. Sometimes, starting with your limitations might be more helpful in making a decision.

So, without further ado, here are Unacceptable STEM Topics/methods from our rulebook:

1. STEM topics that lack a focus are a bad choice for this challenge. Being too broad can end your 3-5 minute film with more questions than answers for your audience. Being specific will also help your project from being overwhelming to you as the film maker.

2. STEM topics that are not based in fact are not acceptable. Remember that citations for your sources are not just required by this competition, but are legally required for research works. We adhere to USM’s academic integrity policy for this challenge.

3. Topics that are not accessible to the understanding of the general public is not advisable. Getting too far into the weeds with, for example, the specifics of nuclear fission with industry-only acronyms and complex equations flying all over the screen is the best way to lose your audience (and, more importantly, your judge.)

4. Any film that lacks sufficient facts that allow the audience to understand the details of the topic is a no-go. “Baby polar bears are very cute,” is not a fact-based statement, but “Newborn polar bear cubs are called ‘coy’,” is.

(Louisville Zoo, louisvillezoo.org/animalsandplants/polar-bear)

5. Relying on people being on-video most of the time will weaken most projects. This detracts from the video, with few exceptions (see 2024 9-12 Grade Division winner “Common Snapping Turtles: The Documentary” for an example of this method being used correctly and effectively). Someone simply reading facts off of a sheet does not make a video an MSFC film (and it doesn’t make for a creative and interesting presentation, either.)

6. Skits about the topic are not acceptable. Think of this project as a research paper set to film.

7. Parody in general is not acceptable. While a parody of Star Wars and the technically incorrect use of light-speed travel throughout the series would be very fun, it isn’t the correct mode of delivering information for this challenge. Don’t let this steer you away from humor, however. Presenting information with humor, as long as the heart of the project is fact-based and researched, can reach your audience’s hearts as well as their minds, and help them understand and remember the information.

Now that we’ve told you no a bunch of times, here are things you absolutely can make your film about:

- Science topics within the disciplines of astronomy, biology, physics, chemistry, health, ecology, energy, etc

- Engineering topics within the disciplines of electrical engineering, biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, civil engineering, etc

- Technology topics that fit within the tools that are used in Science, Mathematics and Engineering

- Mathematics topics within the disciplines of algebra, number theory, geometry, topology, data science, etc

- The history of any STEM topic or historical figure in STEM

If you’re having a hard go of it in picking a topic, or don’t even know where to start, the world truly is your oyster (you could even do a video on oysters…)

You can browse our website to see previous winners and competitors to get a feel of the kinds of things people have made their film about in the past.

Many educators participate as coaches in the Maine STEM Film Challenge to bolster their class curriculum, or to serve as a final project for certain educational units in their Science and Math classes. Going more in-depth about things you’ve learned about in the past are also a great option– for example, if you really want to get into mushrooms and mycology, but your biology classes only covered them for a short period of time, this is a great time to expand your knowledge on something that really interests you.

If you have a vague idea for your film, but narrowing the topic down to something that can be made into a 3-5 minute film is daunting, never fear! Your local libraries are here! We are such advocates of speaking with local/school librarians that we list this resource in the rules twice. They can help you with so much: narrowing down a broad topic into a specific idea, helping you find where to look for your information, and sometimes even help you bring a new idea to light that you previously wouldn’t have thought to study.

We also have a list of resources that will help you narrow down your idea (and to do your research down the line.) Towards the bottom of our MSFC landing page on our website, we have lists of specific disciplines under the STEM umbrella that can point you in the right direction. For example, we’ve broken down Computer, Information Sciences, Programming and Data Science into: computer engineering and architecture, computer programming, data science, network applications, and more.

Other people in your community could be a fantastic source of inspiration and information. Our Planetarium director, John Haley, put the call out on the Planetarium’s Facebook page for those who are interested in an astronomy video so he could give help and guidance. The librarians at the University of Southern Maine’s Glickman Library are also happy to help! You can ask questions about how to begin researching to choose your topic here.

If a historical STEM film sounds more interesting to you, we have a handful of notable people in STEM history on our Resources page.

It doesn’t just have to be professionals, however. The perfect idea can come from a walk in the park with a loved one, or a TV show you love that created an interest in how a machine works. The spark of inspiration can come from anywhere, as long as your eyes and ears are open to find it.

We are also happy to answer any questions about your theme, or the challenge at large. Email us at msfc@maine.edu, or you can directly talk to our administrative specialist Cassidy at cassidy.munley@maine.edu .

“Anyone who creates is a friend of mine.” -David Lynch, director and visionary

Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter

Issue 2

October 27th, 2025

Hello again Film Makers!

This is the second in a series of bi-weekly newsletters that we will be sending out to our team coaches/competitors with news, updates for the challenge, timeline suggestions, and resources for your films.

Click on the flowchart to expand it, and feel free to use this timeline for yourself or with your team. (If you would like this flowchart sent to you as a separate document, please let our administrative assistant Cassidy know at cassidy.munley@maine.edu .)

October 10th’s Newsletter was about Topic Dos-and-Dont’s, and if you missed out on that, it’s been archived here: https://usm.maine.edu/stem-outreach/msfc-newsletter-archive/

Today, we’re going to honor spooky season by talking about the most intimidating step for many of our competitors: research!

Okay, maybe this step is a little more anxiety-inducing than truly frightening, but it can still be hair-raising for some folks. While research (and tracking that research to later turn it into a bibliography) is something many people are doing regularly from 5th grade all the way through college, our kindergarten through 4th grade students may be doing comprehensive research for the first time with this project (in fact, we think this is a fantastic way to make research fun while teaching the fundamentals.) For our adult competitors, this may be the first time in a while that they’ve had to conduct academic research. Wherever you are on your research journey, having a project like the Maine STEM Film Challenge, where you’re researching things that you’d like to be researching, can help build the skill and make it feel less complicated (working toward a really cool trophy can also help.)

The first step in starting your research is to determine what sort of information that you’ll need. We don’t have requirements for how many sources a film has, nor how many of any given type of source that they have, but we do recommend that you diversify your research to multiple source types if that’s accessible to you. For example, you might come across a great article in a scientific journal, which would lead you to a book by one of the authors, then to their Youtube channel.

For younger folks, resources like scientific journals and academic papers from a CAT system may not be accessible for them– whether this is an issue of physical inaccessibility, or the information being inaccessible because it is far beyond their current education level. Diversifying their research may look like a few books from their library, and reliable online resources for children like National Geographic, or NASA Kids science. In turn, research done by someone competing in the Adult Division may have a broad spectrum of sources they can pull from, but may have a harder time filtering that information for validity and applicability to their project.

We cannot ignore the fact that we live in the internet age. That is why how you get your information, and from where or whom, is just as important as getting information in the first place. Remember: films without information that are based in fact are not acceptable for the challenge. The Kentucky Virtual Library has a fantastic guide on how to go through the resource process, including the evaluation of your sources. Stanford has a great Civic Online Reasoning curricula specifically for Science classrooms (though it is applicable to anyone’s time on the internet, researching or not), and it’s free to make an account!

Places like Wikipedia are great starting points, but be sure to be scrolling down into their bibliography to check out those sources for yourself. Wikipedia is a website anyone can edit, so it shouldn’t be the end-all-be-all of your search.

Speaking of things that anyone can edit, we want to give a word of caution for using Language Learning Models (LLM for short) like ChatGPT. The information you get by searching an LLM is not definitive. Depending on the development of the model, the information can be outdated, or even worse– flat-out untrue. If a scientific notion has lots of misinformation attached to it in popular culture, a LLM is far more likely to pull up that information than information from vetted and properly studied sources. While it would be extremely fun to find out that cats were the first animals to boldly go to the moon, Google’s AI feature telling us so does not mean that this is true. In fact, finding correct information through LLMs is extremely hard because it does tend to tell people what they want to hear.

If using AI features in your research, remember that you must cite them properly in your bibliography the same way that you would cite more traditional sources.

Speaking of bibliographies, remember that they’re necessary for this project, so keeping track of the sources you are using for your film is crucial. There are many different methods to keep track of your research. Some people have elaborate sticky-note systems, others simply keep all their links in a Word document. Whatever works for you is best, but it needs to exist in order to work for you. Nobody wants to be in the position of realizing the day before a project is due that they weren’t keeping track of where they got their information– that is something so nightmarish that even Stephen King’s hair would stand on end at the thought.

A great way to log this information (and the method our administrative assistant Cassidy learned studying communications) would be to summarize exactly what it is you want to use from the source with all of the proper citation information, so when it’s time to write your bibliography, it’ll be easier to fill in the blanks instead of starting completely from scratch. For example, if you want to use this article about Jane Goodall for your film, your notes could read “Jane met paleoanthropologist Dr. Louis Seymour Bazett Leaky in 1957 (National Geographic, Sarah Appleton, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/jane-goodall/)”.

This is by no means a proper citation, but it has all of the information you will need to properly cite it later. In addition, it makes it so much easier to refer back to when you are in the Outlining and Storyboarding portion of making your film.

As always, please feel free to reach out to us with any questions! You can email us at msfc@maine.edu, or ask our administrative specialist Cassidy directly at cassidy.munley@maine.edu

“Every time I go to a movie, it’s magic, no matter what the movie is about.” – Steven Spielberg, director and ground-breaker

Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter

Issue 3

November 10th, 2025

Hello Filmmakers!

This is the 3rd in a series of email newsletters that we’ll be sending out to our team coaches/competitors with news, updates for the challenge, timeline suggestions, and resources for your films.

Click on the flowchart to expand it, and feel free to use this timeline for yourself or with your team. (If you would like this flowchart sent to you as a separate document, please let our administrative assistant Cassidy know at cassidy.munley@maine.edu.)

October 10th’s Newsletter was about Topics, and October 24th’s was about Research. You can find those archived here.

Today, we’re going to talk about storyboarding – what it is, and why you might want to use this technique with your team.

What is a storyboard?

A storyboard is an outline for a visual project. It’s used to sequentially break down each shot or element in a visual presentation. It can be used to plan a film’s important scenes, and can include elements such as:

- Drawings or pictures that depict ideas

- Text content that outlines the film narration/dialog (if any)

- Headers or short comments about the purpose or context of each scene

- Notes for production elements

Storyboarding typically follows the script or text outline of a film. The film’s primary focus, story, and flow would typically be constructed before creating a storyboard. However, the storyboard can play a part in the development of the script – you can go back and forth between writing the script/outline and creating the storyboard, using the feedback from each step to make changes & improvements. For a Maine STEM Film Challenge submission, your “script” may just be a document that outlines the topic you are researching, as well as the major “chapters” or sections of your film.

In traditional live-action and animated filmmaking, storyboards play an important role in communicating ideas about the visual elements of a scene. They are used to describe details such as camera movements, actor placement, character actions, and even down to the type of camera lens used for each scene. This is because there are complex ideas that need to be coordinated before a scene is filmed or animated. Completing storyboards helps to organize & visualize ideas, and communicate them in a team environment.

Types of storyboards

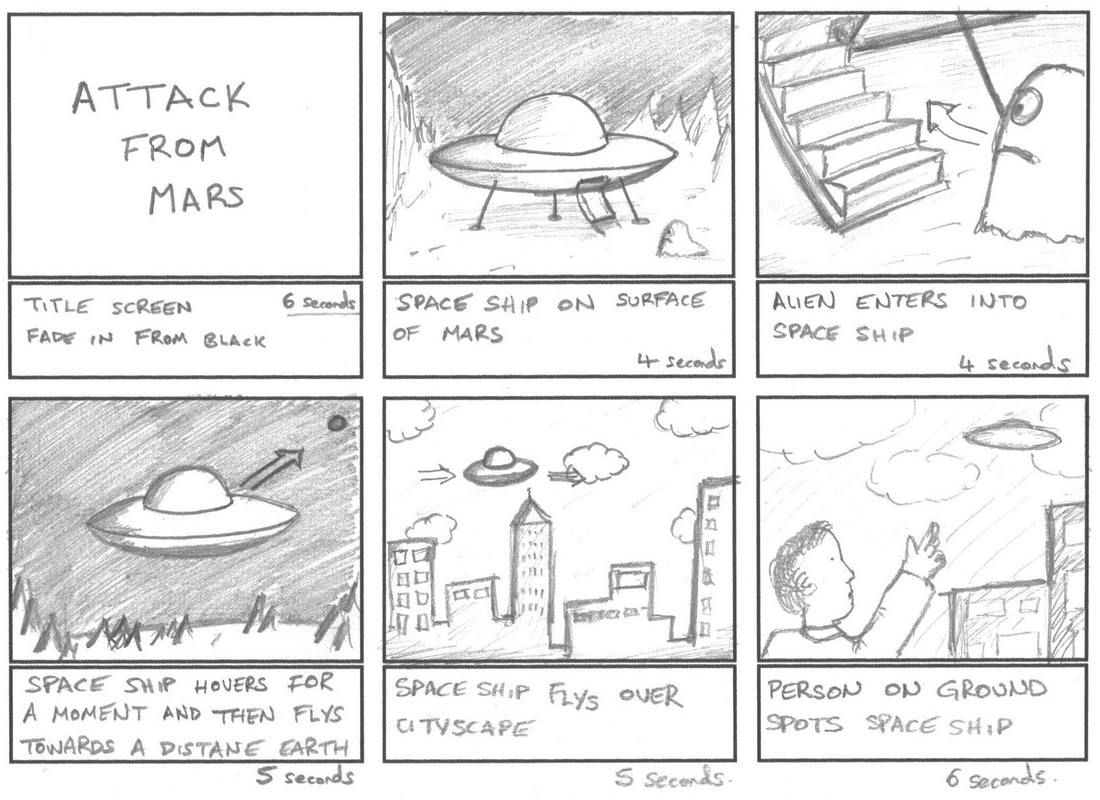

You have probably seen a comicbook-style storyboard that looks like this:

Courtesy of Dream Farm Studios, click here if image doesn’t display

These types of storyboards focus on visual ideas. They include arrows that indicate movement or action, and short sentences that describe the purpose, context, and duration of each scene. Storyboards like this are great for picturing the flow of a video before filming/animating it. Your team may be creating content that would benefit from this, particularly if there are any complex filmed scenes or anything animated.

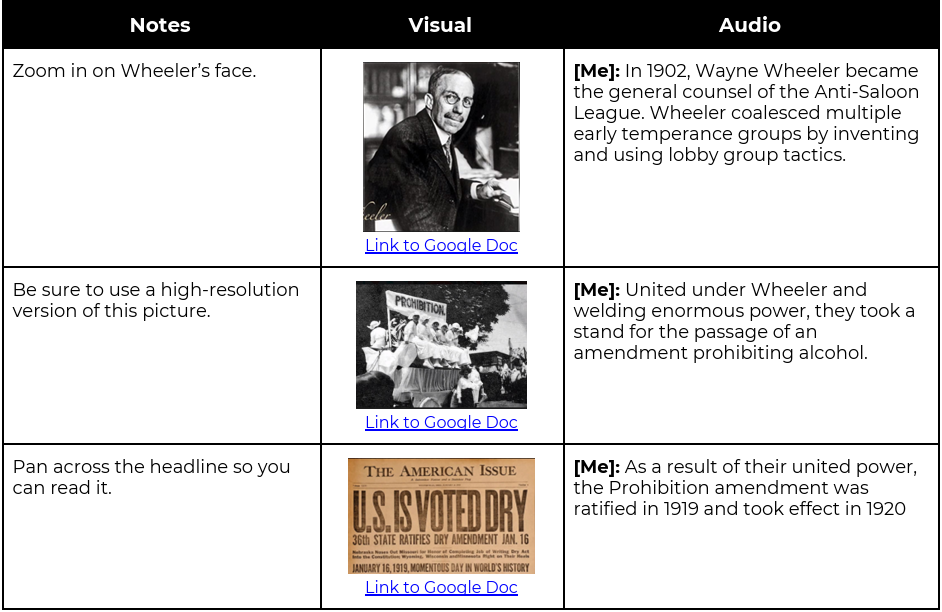

However, many films that follow a more standard documentary-style approach may not see any benefit from using a storyboard like the one above. This is especially true for teams that will be mostly using pre-recorded videos with text & narration. When working with multimedia productions that don’t rely on filming a lot (or any) content, the need for storyboards may seem less obvious. For these types of films, a different approach can be used:

Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, click here if image doesn’t display

Storyboards like the one above are great for:

- Organizing the multimedia elements in your project

- Planning the timing of visual elements with respect to the dialog/narration

- Identifying gaps in the film where more content may be needed

- Creating a collaborative document, where multiple team members can contribute

This type of storyboard focuses less on conceptualizing scenes of a film, and more on organizing audiovisual elements. However, both of the above approaches (or some combination in between) are useful tools when planning a film’s outline.

Why should you use a storyboard?

Though not required, storyboards can be a great addition to the planning process. Maine STEM Film Challenge submissions are graded just as heavily on the “Artistic Delivery” (audiovisual quality) category as they are in the “Content” (script/research quality) category. Using a storyboard or other method to organize your ideas allows your team to take a methodical approach to designing the multimedia portions of the film. It can help your team be intentional about video or picture content decisions, and help identify areas that need improvement. Your team may find it easier to identify which sections need more content when looking at it in a storyboard format – for example, you may notice that a film is using a lot of still images, and it could benefit from a few video clips being added in. From a content standpoint, you may notice that the flow or pacing of the film seems “off” once you look at the film in a storyboard format. This allows your team to step back and make changes to the script or outline before beginning production. All of these aspects can help make the final film feel more cohesive.

Utilizing a storyboard can also help make team collaboration easier. By compiling visual content into one document, team members may find it easier to contribute their own ideas. Having a big-picture view of the flow of the film can also make it easier to delegate tasks among the team members.

Storyboard resources

The Minnesota Historical Society created templates for producing documentary storyboards that align closely with the types of films that are being created in the Maine STEM Film Challenge. Take a look here:

Documentary Storyboard Template

Documentary Planning Framework

If you are interested in creating more traditional storyboards, you can also try this free storyboarding software called Wonder Unit Storyboarder. You can also find a series of tutorials on using this software here: Storyboarder Tutorials

We hope your team considers using a storyboard for their project this season!

As always, please feel free to reach out to us with any questions! You can email us at usmstem@maine.edu, or ask our administrative specialist Cassidy directly at Cassidy Munley

“That’s the way I work: I try to imagine what I would like to see.” – Sofia Coppola, director and niche-definer

Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter

Issue 4

November 21st, 2025

Hello again Film Makers, and a very happy Friday!

This is the 4th in a series of bi-weekly newsletters that we will be sending out to our team coaches/competitors with news, updates for the challenge, timeline suggestions, and resources for your films.

Click on the flowchart to expand it, and feel free to use this timeline for yourself or with your team. (If you would like this flowchart sent to you as a separate document, please let our administrative assistant Cassidy know at cassidy.munley@maine.edu .)

The previous three emails covered Topics, Research, and Outlining & Storyboards. They’re archived here.

For today’s newsletter, we’ll be discussing creating films using mobile phones/devices.

Filmmaking equipment can be expensive and hard to access. Good-quality cameras can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, and professional film cameras can cost anywhere from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars (and that doesn’t even account for the lenses!). However, mobile phones & devices are now frequently equipped with high-quality cameras, and it is increasingly common to see media that was produced solely with a phone. This is especially true for short-form content on social media – think Instagram/Facebook/some YouTube videos, and so on. However, some full-length films, such as Tangerine (2015) and Unsane (2018), were filmed entirely using iPhones (note – these are both R-rated movies, used as an example here due to their relative success, not appropriate to be used as a reference in class for our K-12 participants).

It is entirely possible to capture high-quality video using a mobile phone, and acceptable for many situations – including Maine STEM Film Challenge submissions.

Please continue reading to find out more about how to get the most out of your phone camera.

Considerations when filming with mobile phones/devices

While mobile phones have a lot of benefits such as accessibility, affordability, and convenience, they tend to lack in a few areas when it comes to recording video. Primarily, this comes down to:

- Fixed lenses (no optical zoom)

- Nonstandard aspect ratio

- Lack of storage

- Low battery life

- Low stabilization

- Poor audio quality (!!)

A typical video recorded on a phone is not usually of sufficient quality for use in videos/films, mostly due to the above constraints. However, as mentioned above, phones are used in many different areas of video production. For your Maine STEM Film Challenge submission, you may need to take videos of people, places, or things to augment your submission. With some planning & consideration, it is very possible to get high-quality video from a mobile phone. We’ll cover some tips & suggestions below. Even using a few of these suggestions can vastly improve your video quality. We’ll be focusing on lighting, stabilization, file organization, and audio quality primarily.

Lighting

When it comes to creating high-quality video, the lighting is arguably more important than the camera itself. Most of what contributes to how a video looks is ultimately how well it’s lit. Film lighting is an area of study unto itself, and we are not here to explore its complexities. That being said, understanding a few basic concepts can vastly improve your final product.

Avoid dimly lit areas – As you may already know, video captured in low-light areas results in grainy footage. The reason for this is because the camera overcompensates for a lack of light by increasing the ISO or gain. This amplifies the video signal (making it brighter), but it also amplifies the noise (defined as the inaccuracies in the image capture caused at the sensor level, more obvious when gain is increased). To avoid the graininess, you can simply record in well-lit areas. Natural light tends to be best, but any light that is closer to eye level is ideal. This can mean windows, table lamps, or other sources. If that’s not available, overhead lighting is acceptable – and anything is better than no light at all!

Avoid overly bright areas – Video quality can also suffer if there’s too much light. Although it’s not as much of an issue as not having enough light, you can sometimes have issues with this if you’re filming outside with the sun directly overhead, for example. Consider filming in a shady area or at a different time of day.

Make sure the light is in front of you – Especially when you’re recording indoors, it’s important to make sure that the subject is facing the light source. If not, your video may look darker than expected. Consider a situation where a student wants to capture a video of a teammate for their film submission. They choose a location that has a large window with lots of natural light coming in. However, they position the student being filmed with their back towards the window, and the camera is positioned facing the window. This is called backlighting, and results in the student showing up in the video as a silhouette. Ideally, you would want to try frontlighting – with the student facing the window, and the camera in between. Here’s an example of both situations (as imagined if you were standing overhead):

Capturing sound

Probably the biggest challenge when it comes to recording videos with a phone is capturing audio. Audio recorded from a phone video can be inconsistent, hard to understand, and will tend to have lots of unwanted noise. If at all possible, it would be recommended not to use the audio that’s captured from a phone’s internal microphone in the final film submission. What else can you do?

If you have access to or are willing to obtain an external microphone, that can make a very noticeable difference. External microphones are useful, because it gets the microphone closer to the source that you’re trying to record (and further away from unwanted noise). This results in clearer and more even sound. If you get one that can be connected into your phone, then the resulting video file should have the microphone’s recording embedded directly into it.

Rather than make a specific product recommendation, you may have access to (or want to get access to) a microphone like this:

They are typically referred to as lapel or lavalier microphones, and these are wireless. One end connects to the phone, and the other is clipped to the collar-area of the person talking. The microphone can also be held, but that’s general not recommended. Make sure you keep these kind of microphones far away from your mouth – they are not meant to be used like a typical microphone. You may hear what can be described as “crunchy” audio if it’s held too close. By clipping it onto the collar/chest area of a shirt, it keeps the microphone at an appropriate distance.

However, it’s not always realistic to buy a new microphone to complete projects like these. If the audio from your phone recording is not sufficient, consider muting it or discarding it altogether. If it’s not possible or accessible for your team to get an external microphone, the team can try narrating the film on a separate device. Even a phone that is held closer to the narrator’s mouth, or set stationary on a table, can result in cleaner audio. You can use laptop or tablet microphones (usually built-in) to have the team record someone speaking. This can usually be done in any video or audio editing software. This should result in a separate audio file that can be added to the film submission.

If you need to capture sound other than voice, an external microphone would probably be a really helpful addition. Phone microphones are designed to capture primarily frequencies that are close to the human speaking voice, and are not optimized to reliably capture other sounds.

Stabilizing the video

One easy change you can make that drastically improves video quality is to stabilize the phone that’s recording. Shakiness and unintended camera movement can be distracting. Finding ways to keep the phone camera static can really help.

There are lots of products that exist that serve to remedy this issue. Primarily, you will find 3 major categories – tripods, gimbals, and selfie sticks. Image below:

The selfie stick can be used to maintain a greater distance between the subject and the camera, if being operated solo. Tripods exist to hold the camera in a very static position, and sometimes serve to increase the height of the positioning as well. They also help mechanically isolate the camera from the floor/table/other surfaces, which can stop the video from capturing vibrations (such as footsteps) that may appear shaky. Finally, gimbals are devices that actively stabilize the phone against movement. If the phone is rotated or moved suddenly, the gimbal resists that and keeps the phone steady. These typically function by using center of gravity magic, or by using motors and sensors. I’ve attached a GIF of a chicken demonstrating gimbal properties, as it’s maintaining its head positioning despite forces:

However, you do not need to use a product to get better stabilization in your videos. One simple method would be to prop a phone against an object (a pile of books, a wall, anything really), rather than have someone hold it. Another method would be to create a custom stand for your phone. Do you have access to a 3D printer? If so, there are 3D models available to print custom phone stands that can make it easier to record video. Here’s a few examples: Vertical Phone Stand for Video Calls & Phone Holder Video Stand.

Finally, most video editing applications/software has the ability to stabilize video after it’s been filmed. This is usually available as a feature or a filter. It’s generally accomplished by zooming in on one portion of the video, and discarding the rest. This is a great tool to have if you’re trying to improve a video that’s already been recorded, or if you need to record the video by having someone hold the phone.

File organization

After you put all of the effort into capturing high-quality video, it’s important to keep your video files organized. It can be easy to lose track of files if they’re not named and organized appropriately. Keeping track of the purpose of each video you film is a great place to start.

If you decided to create a storyboard after reading the last issue, this would be a wonderful way to use it. A storyboard may label different parts of the film things such as “introduction”, “section 3”, or even things like “scene 1”, “chapter 2”, etc. Labelling the video files on the recording device in a similar fashion can help keep track of your content.

If you plan on moving the files to a computer/laptop to compile or edit them, there are a few ways to do this. One would be using a cloud storage service (Google Drive, OneDrive, iCloud, DropBox, etc.). You can upload the individual files right from your mobile device onto the cloud, and subsequently download them on the computer that you are planning to edit them with.

However, there can sometimes be issues uploading very large (5-10GB, depending on your bandwidth) files to cloud storage. If you are having these types of issues, consider using a cable to plug a mobile device directly into the computer. Sometimes, this is easy, and sometimes, this can be a multi-step process. I would recommend searching the internet for “<phone model> computer file transfer with a cable” or a similar query to find what the process is for your device.

Finally, there are paid applications you can download for media organization & file transfer services, but we do not have any particular recommendations in this area.

Helpful links

Tutorials:

Record Video With Your Cell Phone – WPI

Best Practices and Tips for Shooting Smartphone Videos – NC State University

How to Film a Documentary on Your Phone: A Beginner’s Guide

Beginner’s Guide to Making Video with your Smartphone – Commons Library

DIY Cinematic Lighting Setup – $50 (YouTube video)

Apple/Android apps:

Capcut – video editing

Canva – video editing

Adobe Express – video editing

Black Magic Camera Free App – expanded camera application

As always, please feel free to reach out to us with any questions! You can email us at msfc@maine.edu, or ask our administrative specialist Cassidy directly at cassidy.munley@maine.edu

“Movies touch our hearts and awaken our vision, and change the way we see things. They take us to other places, they open doors and minds. Movies are the memories of our life, we need to keep them alive.” – Martin Scorsese, director and genre master

Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter

Issue 5

December 1st, 2025

EXTRA EXTRA, READ ALL ABOUT IT!

Hello Film Makers, and happy Monday! Today’s edition of the Maine STEM Film Challenge Newsletter is coming to you because SUBMISSIONS ARE OPEN TODAY!

Starting now, you can register your team & receive your film submission folder!

Click on the flowchart to expand it, and feel free to use this timeline for yourself or with your team. (If you would like this flowchart sent to you as a separate document, please let our administrative assistant Cassidy know at cassidy.munley@maine.edu .)

The previous three emails covered Topics, Research, and Outlining, Storyboards, and Mobile Devices. They’re archived here.

—

This is a quick email to let you know that you can now register your teams! Film submissions are open from now until February 27th, 2026.

Learn more about registering & uploading films here: https://usm.maine.edu/stem-outreach/maine-stem-film-challenge-registration/.

Not ready yet? Don’t worry! We’ve expanded the timeline enough so there’s plenty of time to get started & complete films by the February 27th deadline.

—

As always, feel free to email us with any questions, concerns, or clarifications. You can reach out to us at msfc@maine.edu, or directly reach out administrative specialist Cassidy at cassidy.munley@maine.edu

“Filmmaking is the ultimate team sport.” – Michael Keaton, actor and cultural-shaper