May 11 – July 29

In 2022, Veronica A. Perez was invited to propose a residency project for the University of Southern Maine Art Gallery. They proposed braiding circles — a series of community-based workshops during which participants were invited to braid artificial hair and share the stories that the act evoked. These braids and stories comprise the sculptures created by Veronica and the 2023 Topics in Art course at the University, and are the basis for this exhibition.

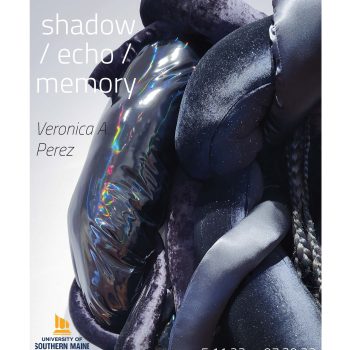

The work of Veronica A. Perez might be described as interdisciplinary sculpture. It also might be characterized as fiber art, community art, or even, at times, horror art. Imposing yet retaining a delicate intricacy, shadow / echo / memory is an immersive installation that subverts the material and scale expectations of the white cube gallery in order to facilitate a needed conversation around fractured identities, representation, and power.

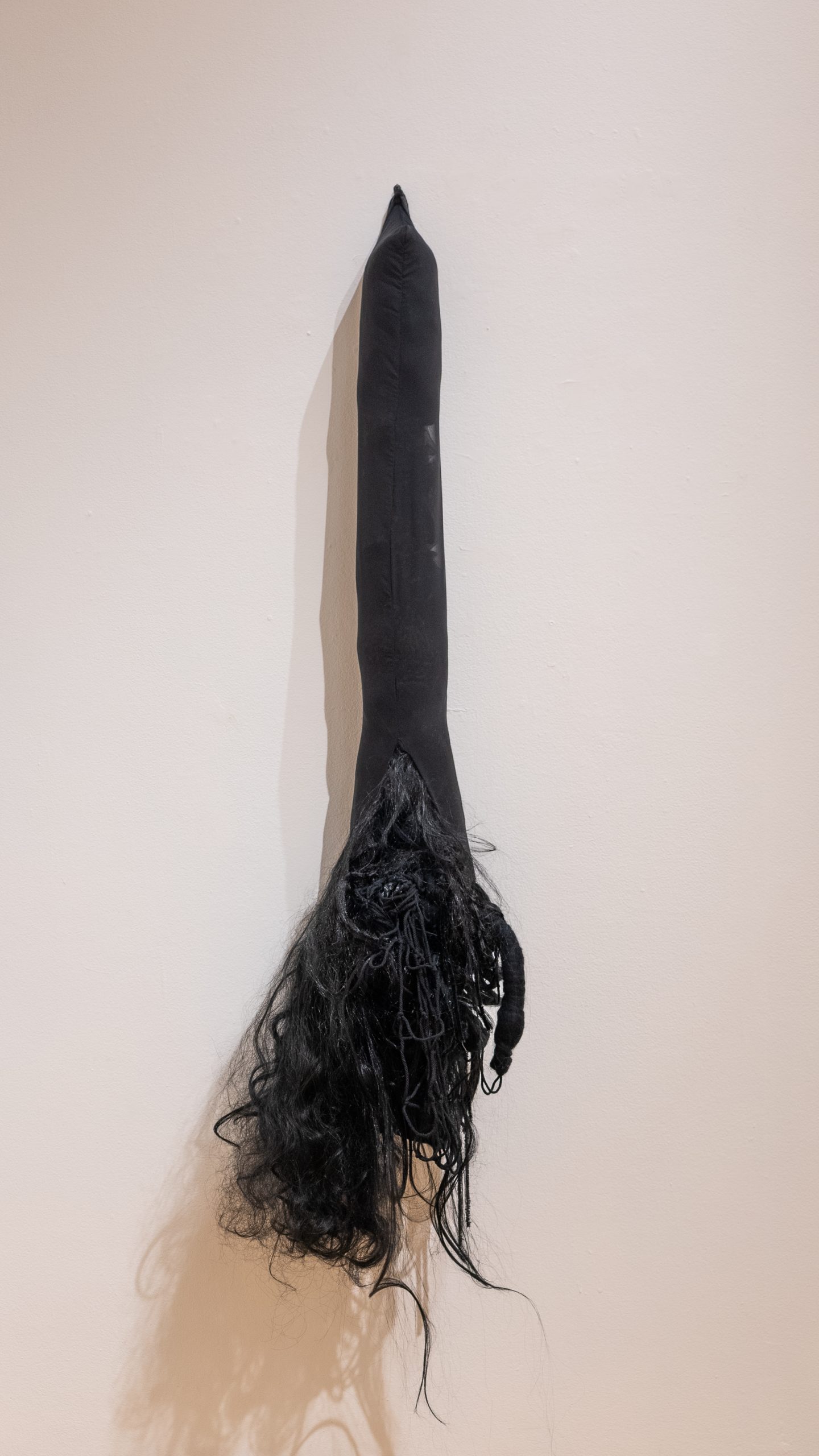

Perez’s work in this exhibition falls into two distinct bodies: large structures primarily comprised of artificial hair intertwined into thousands of intricate braids, and long, cushion-like sculptures which twist upon themselves. Some works resist gravity and snake off the wall and toward the viewer, simultaneously welcoming touch and causing one to recoil. But whenever one tries to define the forms — are they ovular? rectangular? — Perez’s work performs an evasive maneuver, just as it does in-person, perceptually. Masses of braids undulate before our eyes; their unspooling, rippling surfaces beckon as much as they confuse. Perez’s sculptures resist direct observation and reconfigure within our peripheral vision. This ambiguity is strategic, defying easy categorization in order to posit potential futures. This “what am I seeing” hints at the depths of what Perez explores, namely, relationships: between self and family, community and archive, viewer and material, perception and object, labor and rest, and work and gallery.

Perez makes their work with their father in mind. A native Puerto Rican, Perez’s father settled in the Bronx, was drafted into the army, had four children, and passed away at age 60, when the artist was 23. He left very few personal possessions or writing behind, causing Perez to lack a clear picture of who he was. They consider their art to be totems for him. In this framework, Perez’s sculptures become a critical examination of their father, his life, who he might have been, who he might be for the artist, and who he will be for them and the audience that encounters these works. These considerations of family and heritage have led Perez to focus on hair and its ability to braid, bind, and hold memories.

Hair, and the styling of hair, are heavy with cultural significance. Perez’s works contain incalculable numbers of braids, weighing upon one another. As their work grew in scale, the artist involved community participants to braid the artificial hair that comprises their sculptures. Participants discussed the memories while braiding, with conversation naturally flowing from the somatic act. Perez found that repetitive movements allowed practitioners to enter a meditative state and access memories they may not otherwise recall. The artist was compelled to capture these moments and built an oral history archive rooted in the personal experiences of Black, Brown, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian, and Intersectional communities focused on hair. Without Perez’s workshops and the somatic processing they facilitate, these experiences may otherwise never be recalled, archived, or shared. The stories are now incorporated into Perez’s sculptures. Participant memories, and their subsequent sharing via artwork, allow others to experience the link between hair and identity.

In addition to the communally braided sculptures, shadow / echo / memory showcases new directions in the artist’s practice. Thin strands of hair no longer solely compose the braids. Instead, thick, long pillows twirl around one other. The fabrics Perez utilizes in these new sculptures shine and glimmer against a black ground. They recall interstellar skies or depths of the sea in which light fades to a murky shimmer. The artist’s materials mimic the phenomena that envelop us above and below and yet are fundamentally unknowable.

Simultaneously, these cushions imply a need for rest, markedly contrasting with the intricate and tedious labor that created the forms built with artificial hair. The need for rest coils in on itself, reflecting our contemporary condition of tortuous unease with the concept. These new sculptures give their visual weight to labor exploitation past and present and its attendant forbidden relaxation. The horror influence on Veronica’s work here lurks just beneath a pillowy surface. Cushions beckon one in with a promise of comfort. Once engaged, the work provokes an interrogation of what it means to “rest easy,” and who holds us as we sink into form-fitting foam comfort.

shadow / echo / memory combines accessibility through its material elements of hair and fiber with theoretical grounding. Appropriately, three main theoretical underpinnings emerge from Perez’s work: Afro- and Latinxfuturism, which features futuristic themes incorporating aspects of Black and Latinx culture;1 potential history, which calls on us to recognize an alternative, anti-imperialist heritage that our past offers our present;2 and radical imagination, which posits that we imagine institutions not as they are but as they might be, then rescue that theoretical from the future and implement it in our present.3

Through these lenses, Perez’s braids can be understood as representing the past, present, and future, creating a multiverse through their combination. Similarly, the works’ monumental scale speaks to the heaviness that the history of hair styling has today on identity, both personal and cultural. Titles such as hereditary hammer this fact home, with a coiling inescapability of signifiers tying themselves into knots, complicating the legacy of hereditary traits that we hold personally as well as those contained and harkened to by the white walls of the gallery. With the incorporation of first-hand accounts and memories of hair, the sculptures gain multisensorial resonance. Ever-expanding and encompassing, Perez’s sculptures creep toward the viewer and swallow the austere architecture with the weight of first-hand histories made manifest, hinting at depths untold, inaccessible, and unknowable — but whose acknowledgment, memories, and imagination give way to a future that prioritizes joy.

Of the theoretical lenses, Perez has said they most often employ radical imagination. The theory provides the artist with a framework to consider the realities of colonialism, imperialism, and gentrification, and allows the artist to offer a future that acknowledges these elements of our past. Similarly, radical imagination helps Perez to consider the lives that their father could have led, using the past and the present to imagine a new future. They say, “Just imagining Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx people in the future is really important. It shows us that we still exist.”4

— Kat Zagaria Buckley, Director of Art Exhibitions and Outreach

1 Afrofuturism was first coined by Mark Dery in “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” in Dery, Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994), 180.

2 As theorized by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay in Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso Books, 2019).

3 Adrienne Maree Brown’s “Closing Remarks,” in Fall Retreat (Environmental Grantmakers Association Conference, New York, NY, 2015), provide important context here. https://adriennemareebrown.net/2015/09/30/closing-remarks-to-environmental-grantmakers-association/. Additionally, Brown’s Emergent Strategy figures into much of the thinking in this piece regarding networks: Brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, Reprint edition (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2017). See also the interview with Silvia Federici and essays by Isaac Saney and Sherry Pictou in Alex Khasnabish and Max Haiven, The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity (Halifax; Winnipeg: London: Zed Books, 2014).

4 Veronica A Perez, A Conversation with 2023 Artist-in-Residence Veronica A. Perez, interview by Kat Zagaria Buckley, February 14, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioGcJX-Uu3A.

Artist bio

Veronica A. Perez is a multidisciplinary artist living in Maine. She utilizes synthetic hair, discarded objects, and other unconventional materials such as sugar and construction remnants in their sculptural works to conceal and reveal hidden and forgotten parts of ones’ identity. Perez creates intense personal moments by means of material hybridization and challenging ideals of beauty. Her chosen material aims to comment on contemporary Latinx and feminist issues which they explore through notions of loss, time and trauma. In 2020, she was awarded the Ellis-Beauregard Fellowship in the Visual Arts and in 2021 began her residency at the David C. Driskell Black Seed Studio Fellowship in Portland. She was one of the inaugural Lunder Institute for American Art fellows at the Colby Museum of Art. In 2022, Perez presented her first solo exhibition at the Center for Maine Contemporary Arts in Rockland, Maine.

Exhibition Gallery

Perez is the 2023 Artist-in-Residence at the University of Southern Maine Art Gallery.

This program is made possible with generous support from The Warren Foundation, the University of Southern Maine Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity Council, the University’s Center for Collaboration and Development, and the University’s Women & Gender Studies Department. Funded by the Maine Humanities Council and the Maine Arts Commission.