October 9 – December 5, 2025

Crewe Center for the Arts

111 Bedford Street

Portland, Maine 04103

The Crewe Center for the Arts Great Hall Gallery’s inaugural exhibition will feature the work of the Art Department’s newest faculty member, artist Janna Ahrndt. Tying together themes of technology and what makes us human, Ahrndt’s work offers a whimsical and at times humorous interrogation of the “efficiency” promised through automation across various domains, including memories, cleaning appliances, Furbys, and more.

Curatorial Essay

Janna Ahrndt’s work undermines oppressive systems of surveillance capitalism, artificial intelligence, and patriarchal dominance by using humor to poke holes in the veil that obscures these structures from critique. Her primary methods of investigation are dismantling, hybridization, and building anew but askew. Ahrndt’s work allows for a recognition of the ways that contemporary culture has internalized the stories technology tells about itself. In doing so, she reveals the propaganda that surreptitiously curls its fingers around the edges of narratives of progress.

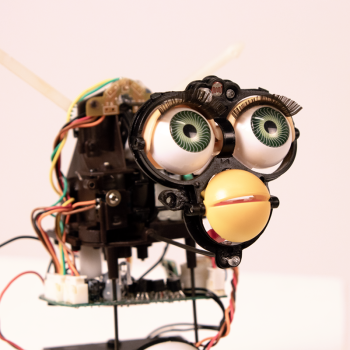

In BigData Church Ahrndt works with the Furby, a nostalgic ’90s gadget. She strips away its fur and body, leaving behind only a robotic armature and eerie face. Its large green eyes and absurd, uniform eyelashes invite anthropomorphic identification with the machine’s childlike features. Its beak subtly clashes with the eyes in a delightful way that is still easily digestible for children, creating an infant animal of hybrid origins. The toy’s resulting owl-like face is inherently at odds with the exposed metallic, articulated skeleton, typically hidden under a shroud of plush, brightly-colored artificial fur. Each day, BigData Church gives a prediction to audiences. Its divinations are underpinned by the technology that ran ELIZA, a chatbot that debuted in 1966. Through this sixty-year-old technology, Ahrndt smashes together the writings of Nostradamus, prophecies from the Oracle of Delphi, and contemporary headlines, which the Furby spits out at auspicious times of the day, such as 11:11 AM.

The Furby is not a blank slate onto which Ahrndt projects chaos. It is a robot that starts its life speaking “furbish,” but is programmed to say English words and phrases over time, mimicking language development. At its market introduction in 1998, there was a wider cultural paranoia around surveillance that became fixated on the Furby. The public received its innovation as “spooky;” stories abounded of the toys being transmitter devices through which the CIA could spy on unwitting American families. The dolls sometimes seemed to speak, blink, or move their eyes when ostensibly turned off. Interpretations of the Furby’s perceived animation ranged from its movements being an artifact of the government tapping into the device to download its data, to a more routine object haunting — none of which portended feelings of safety.

The Furby is the smart-speaker’s silly parallel, showing a behind-the-curtains look at the ridiculousness of technology. Its ELIZA programming is a precursor to the large language models (LLMs) of today, pulling from a mish-mash of inputs and spitting out a garbled version of sources that the machine cannot verify. Importantly, like the LLM, the Furbish Oracle cannot create material anew. Predictions of the future, given such an uncanny and disarming form, belie the ways in which we place our trust in contemporary technologies to give accurate information. We beseech software to exceed our knowledge and do what we cannot: peer beyond the horizon, predict the future. And yet, the technology we use has its own limitations, biases, and paranoias baked in. LLMs are worse than we are at value judgements, as the ever-flawed human data set of the past forms the basis of their “speech.” In truth, BigData Church is a mirror of contemporary anxieties and desires, a displacement of neuroticism into object form. We are still, across AI and robotic toys, creating in our own image. The outcome of these products, despite their association with paranoid delusions and fervent desires, fails to eclipse the earthly tether of our limited scope of knowledge. We may perceive ourselves as operating in technology’s shadow, but in truth, the technology industry and its products are squarely within our sphere of influence.

BigData Church is but one instance of Ahrndt thinking deeply about where the object and the digital intersect, where the tangible and the intangible intermingle. Her work Digital Sentiments Server, created in collaboration with artist Christine Bruening, looks at the digital preservation of memory. It features three-dimensional scans and three-dimensional prints of Bruening’s family heirlooms, creating a referential archive of every facet of material texture, including chips and cracks. A personal server houses these digital scans, sitting alongside the recreated objects in the Gallery.

Digital Sentiments Server raises questions around the necessity of the object for conjuring memory. Digital twins of Bruening’s heirlooms are frozen in time, before their stains wear deeper, their chips and fractures deepen under the pressure of display and concomitant endangerment in the home. Digital conservation creates replicas at a greater distance from the originals when compared to traditional methods of reproduction. When an original object’s aura derives its strength from its pivotal and deeply personal placement within our lives, the reproduction of said object holds a heightened sense of falsity. Its separation grows in proportion to its removal from the interactions that bred its sentimentality.

The reproduction operates far from the original because of its divorce from the indexical experiences that engender memory. Digital Sentiments Server asks: Where do we keep our archives? Objects themselves are containers; they can physically hold and conceptually be repositories of memory — especially when that object is an urn, a final resting place (one of Bruening’s items in Digital Sentiments Server). The work also harkens to issues around methods of digital preservation, asking if the practice’s outputs are acceptable substitutes in the tangible world. Object copies can be conjured should an heirloom be lost or destroyed. Replication opens possibilities of repair across structure, memory, and time, enabling the proliferation of the uncanny object. Digital preservation maintains a haunted form, a husk of the original lacking the auratic infusement borne of time and presence from an object that lives its life alongside ours. And yet, these husks of after-objects fill a need. Through them, approximations of originals are accessible long after the owners — who are themselves embodied repositories of familial archives — have passed on.

The housing of this archive on a personal, digital server aligns with the exhibition’s theme of evading technological surveillance. With technological conglomerates controlling access to our digital memory repositories, we are confined, without any input or control, to extractive co-stewardship relationships. Bruening and Ahrndt propose the personal server as a means of circumventing corporate ownership of our memories and musings.

The final consideration of surveillance in the exhibition that I wish to examine is Ahrndt’s Captivate & Engage. Each of these objects takes the form of the traditional cleaning apparatus. The artist spray-painted the machines to resemble the bombs. The flags are of Ahrndt’s own design, combining tropes of vexillological symbolism with flat blocks of color. A hole at the back of each machine allows viewers to peer in, peep show style, at benign, non-military aerial drone footage of landscapes.

The vacuum cleaner, since its introduction, has created more work in the house despite being heralded, initially, for its time-saving qualities. Cultural expectations of cleanliness and our barometers for its measurement increased accordingly with the advent of the dust suction machine. It bears noting that the labor for achieving a sterile home falls disproportionately on the shoulders of feminine bodies (as does the maintenance of familial heirlooms). The vacuum is an embodiment of the paradox inherent in technology marketed to and accepted by consumers as time-saving innovation when the product, in fact, exploits a subjugated class.

The video format in Ahrndt’s vacuums is ubiquitous in contemporary life, rendering our horizontal topographies digestible; it is also related to the aerial projectile, whose precise drop now depends on the footage. The video’s horizonless view-from-nowhere lends Ahrndt’s objects a consideration of borders. She combines these disparate pieces to lay bare the futility of our technologies: machines and the ideologies they reinforce a Stockholm syndrome-esque belief in their indispensability. The mechanized eye is indiscriminate; its gaze imbues all it watches with techno-cultural hegemony and oppressive ideologies at the behest of a patriarchal nation-state while its most consequential and subjugating values blanket territories.

Janna Ahrndt Does Not Dream of Labor relates these concepts of mechanical futility to the workplace. At a time when technological progress seems to be breathlessly on the cusp of freeing society from labor’s drudgery, we would do well to consider how computerized promises and the feverish fantasies that surround them are often exaggerated. Ahrndt does not dream of being freed from the labor that the machines purport to take on; instead, she envisions a world where we recognize the gaps technology creates when it purports to fill a need. In other words, she does not dream of AI’s transformative promise to work because she does not dream of labor. Ahrndt dreams of actual fulfillment outside of the capital-derivative systems within which, through its own enraptured intertwinement, technology remains entrapped.

— Kat Zagaria Buckley, Director of Art Exhibitions and Outreach