Just as kids today dream of accompanying Harry Potter to school at Hogwarts, the University of Southern Maine campus in Gorham held a special allure to young readers of 100 years ago.

A fictionalized version of campus is one of the main settings in “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm,” by Kate Douglas Wiggin. The novel was a breakout success upon its publication in 1903. It’s a coming-of-age story that promotes the virtues of intelligence and positivity as exemplified by Rebecca Rowena Randall.

Wiggin used her own childhood memories as the basis for much of Rebecca’s world. Many of her observations about campus life ring just as true today as they did when the book was first published in 1903. She describes the hand-me-down dorm furnishings, student rivalries, and the hubbub around graduation:

“There was an excitement so deep and profound that it expressed itself in a kind of hushed silence, a transient suspension of life as those most interested approached the crucial moment.”

Instability defined Wiggin’s early life. She was born in 1856 in Philadelphia. Her father died when she was barely old enough to remember him. The family moved to her mother’s home state of Maine and put down roots in Hollis. At 13 years old, she enrolled as a boarding student at Gorham Female Seminary on the grounds that USM now occupies.

USM didn’t yet exist when Wiggin attended school circa 1869. Since 1806, the campus was home to a private academy school, which offered a rough equivalent to modern secondary education. Upon the school’s closure in 1877, the state acquired the campus and redeveloped it for college-level instruction.

Wiggin only attended the seminary for three terms, but it left a lasting impression. In her novel, Rebecca attends Wareham Academy. Wiggin erases all doubt about the correlation between the real and imaginary schools in her autobiography, “My Garden of Memory:”

“I have paid my respects to this institution in ‘Rebecca,’ never as to facts and real experiences (my invariable custom), but as to externals.”

If transported to the present day, Wiggin would still recognize parts of the USM campus. The schoolhouse where she attended classes is now called the Academy Building. Art students use its rooms for studio and exhibition space. However, the exterior — from the white clapboard siding to the steepled roof — looks much the same as ever.

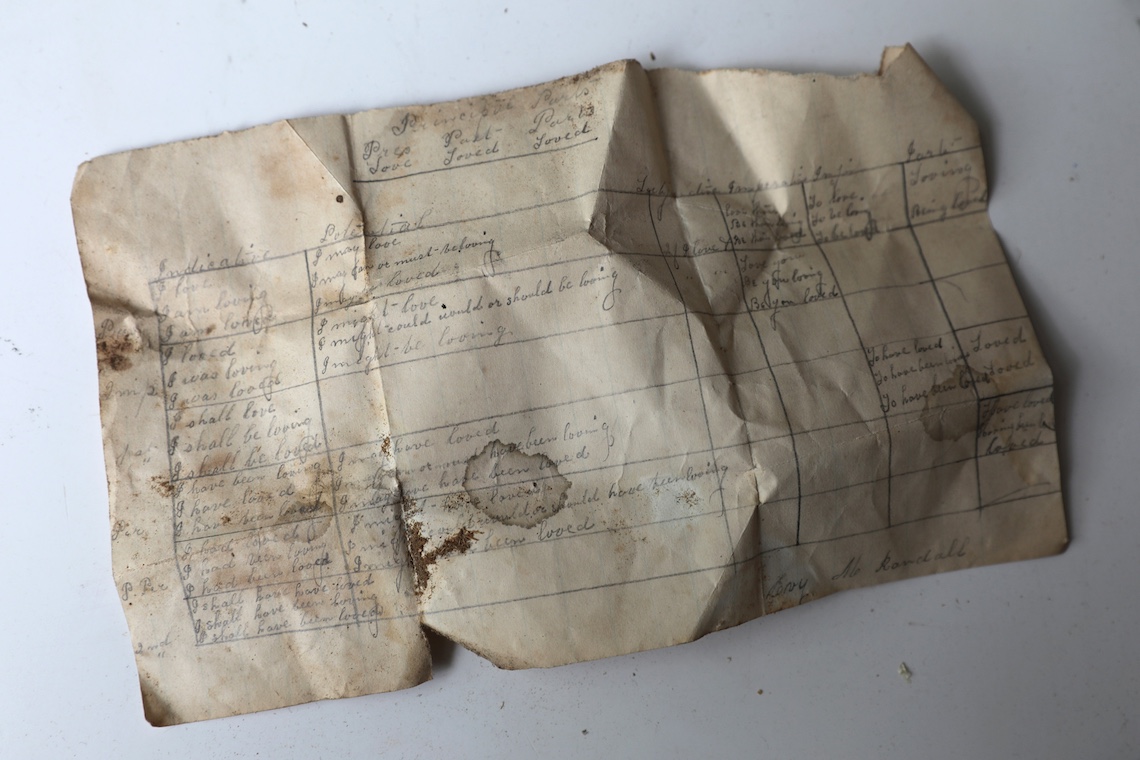

The Academy Building underwent a major renovation last year, during which the workers tore into a wall and found heaps of discarded paper behind the panels. A page from a ledger was dated 1873, near to Wiggin’s time at the school. The scraps also included homework samples that closely resemble the kinds of exercises that Rebecca practiced:

“Full to the brim as she was of clever thoughts and quaint fancies, she made at first but a poor hand at composition. The labor of writing and spelling, with the added difficulties of punctuation and capitals, interfered sadly with the free expression of ideas.”

Wiggin voiced similar complaints about her real-life schooling. She wrote in her autobiography that the seminary wasn’t performing up to its earlier standards in those later years before its closure. She made the best of it by winning an elocution competition and several class prizes.

Like her creator, Rebecca distinguished herself in school as shown by her selection as assistant editor of the student newspaper and graduation speaker. The help she received from her favorite teacher was key to her growth. Mary Smith was the teacher who filled that role for Wiggin at the seminary.

“Under her tutelage, my eyes saw new beauty on every side,” Wiggin wrote in her autobiography. “She developed my natural love for books and taught me discrimination, gave me a fresh sense of harmony in words and opened my ears to poetry.”

Wiggin’s praise carried an expert’s weight. When she launched her career, she was more focused on teaching than writing. She moved to California, where she became an advocate for early childhood education and fought to open kindergarten programs across the state.

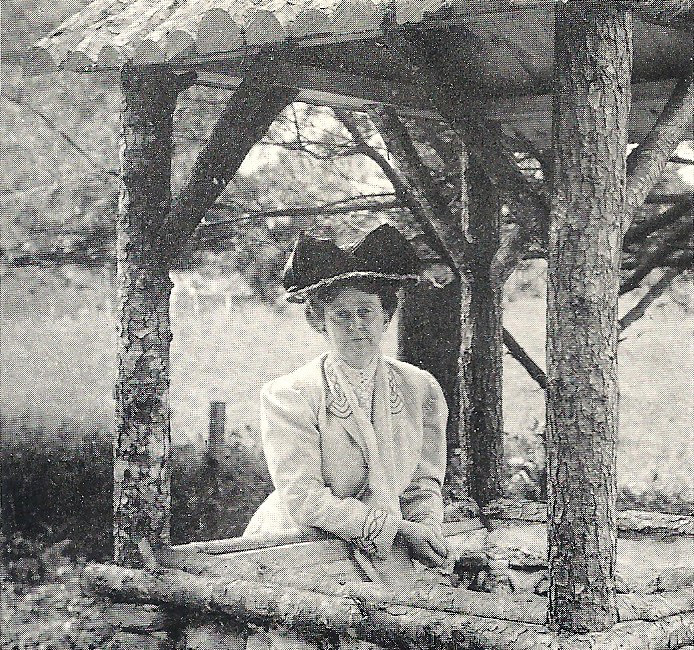

Travel was another of Wiggin’s passions. She crisscrossed the country to promote both her writing and educational views. As her fame grew, so did her mileage. She made several trips to Europe before the advent of commercial flights across the Atlantic Ocean. But of all the places she visited, Maine held special significance.

Wiggin’s success allowed her to buy a home in Hollis. She called it Quillcote, after the quilled pens that symbolize her profession. True to its name, she wrote several stories there including “Timothy’s Quest,” “The Village Stradivarius,” and “The Nooning Tree.” She was on the go the rest of the year, but her summers were reserved for Quillcote.

“I had a favorite place as a child. In times of trouble, you would go back there, or in times of crisis or questioning. It’s just the place that you find peace,” said Nancy Ponzetti, president of the Buxton-Hollis Historical Society. “(Wiggin) did spend a great deal of her life here in Hollis, and even though she did travel, she always came back here.”

A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities allowed Ponzetti to pursue her interest in Wiggin. She collected her findings in a research paper and revisits her studies with occasional lectures.

At the request of visitors, Ponzetti will gladly open the society’s Wiggin holdings, including books, photographs, and newspaper clippings. They attest to Rebecca’s huge multi-media popularity. Wiggin adapted the book into a play. Then from 1918 to 1938, Hollywood released three film versions starring such big names as Mary Pickford and Shirley Temple.

Popularity breeds imitation. In 1903, Wiggin introduced her 11-year-old heroine who goes to live with a strict aunt in a small town. Five years later in 1908, “Anne of Green Gables” came out, featuring another plucky 11-year-old, another stern caretaker, and another closeknit community. The pattern repeated yet again in 1913 with “Pollyanna,” only this time the girl was 12 years old.

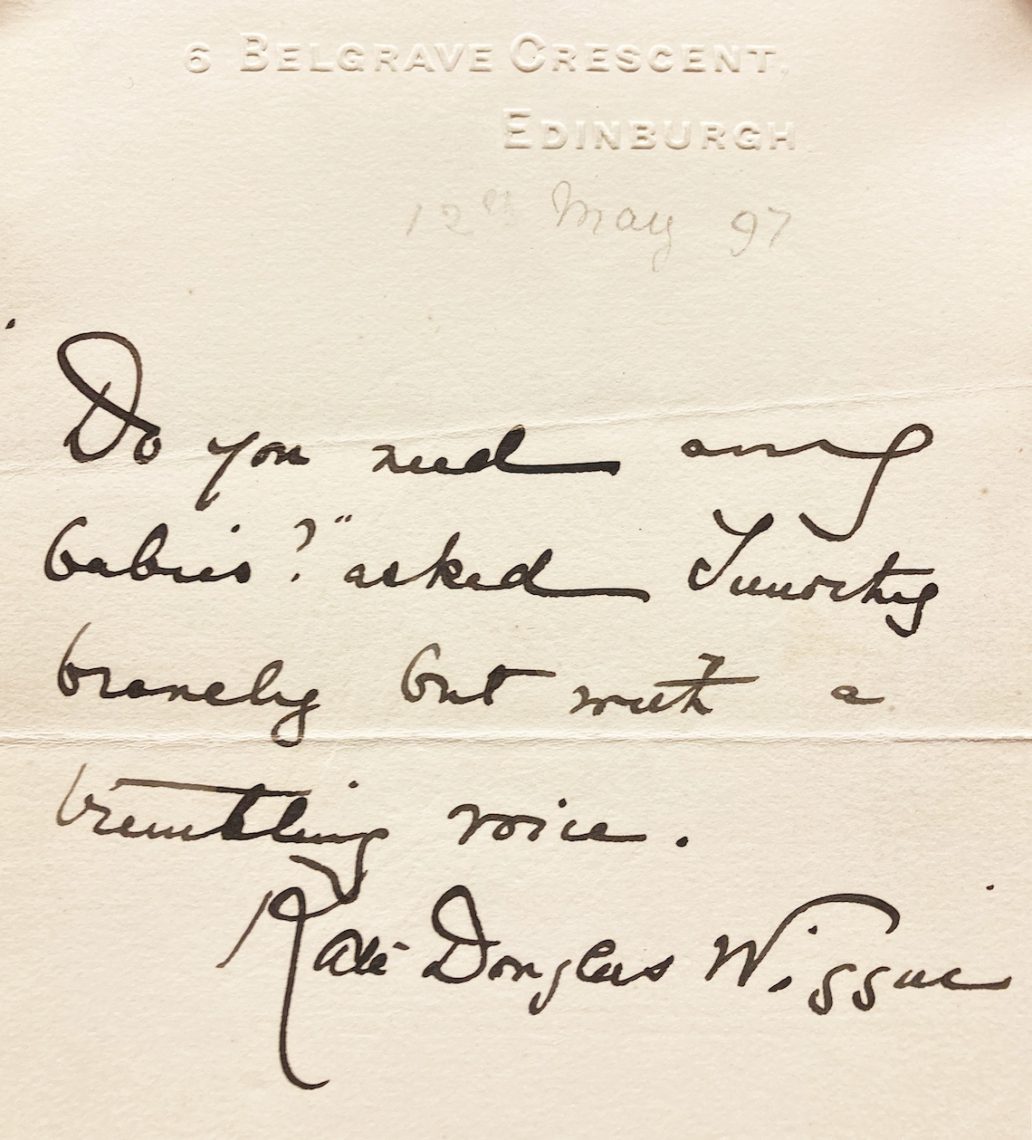

Wiggin counted many famous writers among her fans. Mark Twain, who minced no words about his disdain for Jane Austen, hailed Rebecca as “beautiful and moving and satisfying.” Jack London was even more effusive. He found time to write a letter to Wiggin while working as a reporter during the Russo-Japanese War:

“Rebecca won my heart. Of course, I have laughed, but I have wept as well. She is real; she lives; she has given me many regrets, but I love her.”

But that popularity wouldn’t last. In addition to her duties at the historical society, Ponzetti worked for 22 years as a teacher at Catherine McAuley High School in Portland. She found that the sentimentality of Wiggin’s writing didn’t appeal to her students’ modern sensibilities.

Even USM students who walk the same ground that Wiggin once tread aren’t familiar with Rebecca. The story was new to Jenna Vallance when she encountered it while working toward her certificate of advanced study in Literacy Education.

Vallance was assigned to study a map from 1925 that shows where fictional places are supposed to exist in the real world. Maine’s contribution to the map was Sunnybrook Farm. Vallance had never heard of it before but set out to learn more, ultimately producing a class presentation about Rebecca and Wiggin.

The Harry Potter series and Nancy Drew mysteries were Vallance’s preferred childhood reading. At the Rowe School in Yarmouth where she teaches first grade, her students like to read about Pete the Cat or books by Mo Willems. The settings of those stories are vague, in contrast to Rebecca’s early 20th century setting with horse-drawn carts and petticoats.

“Those are big hits with the kids because they’re just kind of silly and lighthearted and funny,” Vallance said. “And when I think about moving forward, I feel like those might still be relevant to kids later down the line because they’re not really based on a certain time period.”

Dr. Melinda Butler is the chair of USM’s Department of Literacy, Language, and Culture. If she were drawing up an elementary school curriculum, Rebecca wouldn’t make the reading list. Butler favors reevaluating past favorites to make sure they resonate with the tastes and values of contemporary readers.

There is always the possibility that Rebecca will enter the classroom through independent reading, which Butler encourages to supplement course requirements. The student who chooses it might be surprised to find colonial and racial views that were prevalent in Wiggin’s time.

“That would be something that we would stop and at least analyze and talk about and critically reflect on,” Butler said.

On a personal level, Butler also found much to enjoy in a recent reading of the book. She collects books by authors from Maine and owns several titles by Wiggin. Her favorite is “Susanna and Sue” for its depiction of life in a Shaker community. Her copy of “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm” is a third edition from 1917.

Rebecca’s empathy stood out to Butler. The relationships that Rebecca forges with her Aunt Jane and her elderly neighbors help the adults deal with their long-buried grief. Butler also liked the book’s ambiguous ending, which allows readers to choose for themselves what the future holds for Rebecca.

“I thought the writing was lovely,” Butler said. “I thought (Wiggin) wrote with such description.”

Though best known today for Rebecca, Wiggin wrote enough books and short stories to fill several shelves. They do just that at USM’s Glickman Library in Portland. The titles in the Edith C. Rice Collection of Children’s Literature span her career. Most are not available for borrowing and can only be viewed at the library, including a first edition of Rebecca.

Wiggin’s legacy seemed assured when she died in 1923. None of her accomplishments are listed on her memorial stone at Tory Hill Cemetery in Buxton. But glimpses of her life are easy enough to find in the surrounding area.

The Academy Building at USM remains a center of learning, not so different from Wiggin’s student days. And the home fires are still burning at her beloved Quillcote, which is now privately owned by another family.

“I would love people to come. If it was up to me, I would put a sign in front of Quillcote (that reads) Home of Kate Douglas Wiggin,” Ponzetti said. “And if you don’t know who she is, come and ask us at the Buxton-Hollis Historical Society because she did a lot. She did so much.”