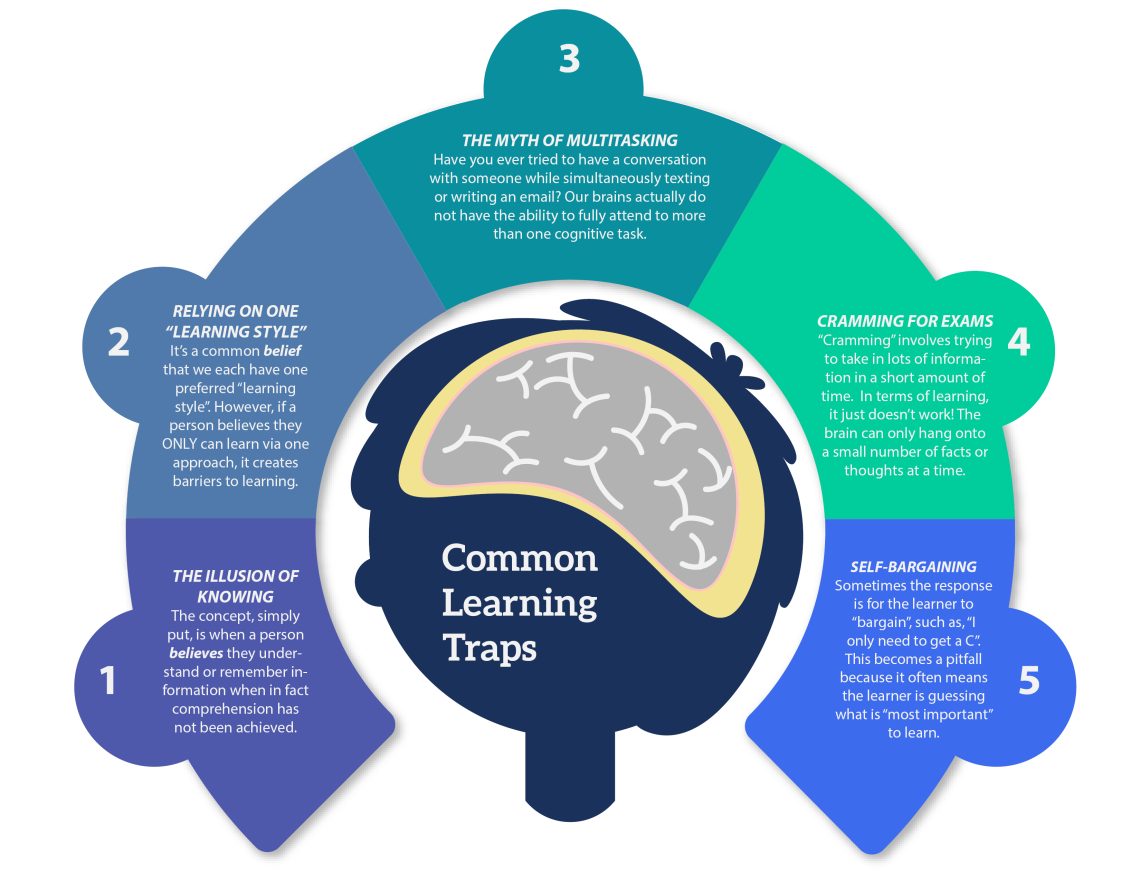

Top Five Learning Traps

Here are ways the illusion of knowing play out in the learning process. We encourage you to imagine the following:

I’m preparing for an exam, starting with a review of my notes. The notes look familiar, so I tell myself, “Yup, I know this stuff.” I take a look at my textbook, and see how I highlighted much of the information; since I’ve read it before, and it looks familiar, I again tell myself, “I know this stuff.” Perhaps I ask the professor or a peer from class to show or explain a concept, and when I see it my brain tells me, “I’ll be able to remember that.” The day of the exam arrives, and when I see the questions, I realize I did not actually KNOW the information.

To avoid the illusion of knowing, it’s important to use self-testing strategies, many of which are explained in this website. Examples include annotating the chapter or article while reading, summarizing key points from a lecture right after class, explaining concepts to others during group study meetings, and creating mind maps to show how concepts are connected and determine what can be recalled and what still needs more review.

Imagine the following:

I go into the first day of class, believing I’m a visual learner, and the professor announces the plan to rely on auditory lectures and small-group discussions. My response may be, “I’m not going to be able to succeed in this class!”

Here’s the reality: the most recent research on learning indicates that the most successful learners use SEVERAL approaches to learning, not relying on one strategy. The more approaches the learner takes, the greater the level of understanding and memory. In the class example above, a person who recognizes the value of visual learning can use active note-taking strategies to create visual representations of the concepts. The key is to not limit oneself, but rather to use many tools and approaches to learning.

Have you ever tried to have a conversation with someone while simultaneously texting or writing an email? How about sitting in class and having a browser open on the laptop to read a website or watch a video while “listening” to what the professor is saying? Our brains actually do not have the ability to fully attend to more than one cognitive task.

Why is this important to being an effective and efficient learner? Because when we multitask while trying to learn, some of the information never “gets into” our brain since we are not paying full attention. When it comes time to prepare for a paper, a lab, or an exam, we often realize we have gaps due to this lack of attention, forcing us to go back to “learn” that information again. This is a tremendous waste of time, especially for a busy student. The key to avoiding this pitfall is to “single task.” Single-tasking entails removing distractions (people, phones, social media, etc.) and committing to pay full attention to the one academic task at hand.

Why doesn’t it work? The brain can only hang onto a small number of facts or thoughts at one given time. Cramming also does not create the opportunity for the brain to actively make connections between concepts, or to allow the downtime known as a diffused learning state, in order for the brain to “digest” the information and find the connections. Most learners become fatigued after a few hours of academic time on task, so the longer a person spends cramming, the less effective and efficient it becomes. Also, cramming typically involves memorization, and at the college level, the need is to UNDERSTAND and COMPREHEND in order to APPLY concepts, not just remember them.

Instead of cramming, spaced practice is the key. This means scheduling several “swipes” with the information throughout the week, not just before an exam. It also means using active learning strategies to make connections, test for memory and understanding, and to create the “scaffolding” or foundation of memory upon which new information from the class will be built as the course progresses.

Bargaining is about self-talk, so paying attention to this internal dialogue is one of the best ways to avoid this learning pitfall. Messages such as, “There’s no way I’m going to do well in this course” or “I don’t have time to do that much reading” can be challenged. EVERY STUDENT can succeed by managing time effectively, planning out the academic time on task for the semester, engaging with the reading and other course materials, and self-testing. Setting a high goal paired with daily effort towards that goal leads to success!

Video: Introduction to Spaced Practice

Exam Preparation Tips

All effective learning requires practice. “Practice” involves:

- Action: While watching and listening introduces information into the brain, it is the DOING that moves the learning process forward. Consider the skill you listed above: would you have that skill if all you did was watch and listen?

- Repetition: Information must be “worked” more than once for it to form a neuropathway in the brain. In other words, repetition CREATES memory.

- Feedback: Many people do not seek out suggestions or constructive criticism from others. It is this information, though, that allows a person to go to the next level of performance or understanding, to get “unstuck” or overcome obstacles.

- Reflection: When attempting to learn, repeatedly checking for understanding and competency is a vital part of the process. Ask questions along the way, such as: How am I doing? What is it I know and can do well? What am I finding to be challenging or do not know?

College students need to be able to learn multiple subjects, concepts, and skills in the same semester. While there is a significant time management component, the following guidelines will help you make the most of your practice time.

Spaced Practice

“Spaced” refers to the frequency of the practice. It means practicing more than once during the week and allowing space in between the practice sessions. Once a week is not enough to build a skill, and trying to cram in lots of practice in one day results in fatigue, not productivity. Spaced practice takes finding several shorter times throughout the week, such as 60 minutes on Sunday, 60 minutes on Tuesday, and 45 minutes on Thursday. This “multiple-swipe” approach builds memory, understanding, and skill far more quickly, and creates durable learning, learning that will last over time. (Ideally, these practice bursts should be happening weekly, not only right before the exam!) For guidance on how to incorporate this strategy into your exam preparation, watch our Spaced Practice video!

Active vs. Diffused Learning States

Many learners focus on the active part of learning: attending class, taking notes, reading the assigned materials, studying in groups, and doing practice problems. These all entail paying attention, and consciously trying to learn, understand, and do. There is, however, another important learning “state” of mind: diffused learning. Imagine the following:

In the moment, I’m struggling to remember something. Later, when I’m on a long car ride, going for a run, or about to fall asleep, the answer suddenly hits me with an “Ah HAH!!!” out of nowhere.

THAT is an example of the diffused or “resting” learning state. While not ACTIVELY thinking about the concept or trying to remember, the brain continues to connect information and make meaning during times of rest and quiet. By “rest and quiet,”, it does not necessarily mean laying down or meditating; rather, it refers to having time throughout the day and week designated for something other than active thinking. This is why it is so important to find a balance between enough active time on task and non-studying, self-care time. Part of “practice,” then, is the intentional “off” time.

Single Tasking

As mentioned above, a common learning trap is the notion of multitasking. Whether having a conversation, listening to a class lecture, or watching a movie, our brain is taking in information. If this is paired with taking out your phone to play a game, text, or browse social media, the brain’s attention is split between more than one set of stimuli. The brain does not have the ability to effectively multitask, and the more often you do this, the more you are forcing the brain to pay less attention to any one thing. Think back to the skill you had in mind earlier. If attempting to focus on something else while “practicing” that skill, how effective would that be? The reality is that it would likely waste time and effort, add to your frustration, and reduce the likelihood of peak performance.

By single-tasking, you are building more efficient brain chemistry, priming the brain to get the most out of every learning situation. This saves time as well as maximizes the learning effort. Single-tasking entails removing distractions, committing to pay full attention, and actively trying to connect new information to what the brain already has understood, experienced, or remembered. An effective approach that can assist with single-tasking is the Pomodoro Technique. This widely used time management method was developed in the 1980’s by Francesco Cirillo, and continues to be a favorite amongst USM students. Watch our Pomodoro Technique video for step-by-step guidance with using this effective approach as part of your exam prep!

Retrieval Practice

While spaced practice is about the when, retrieval is more about the what: the content. Retrieval practice involves intentionally trying to “go get” relevant information in our brain to apply in the present. Each time we retrieve, our memory of the information becomes stronger. For example, instead of just reviewing concepts from the most recent week of class, ask yourself, “What information or concepts from earlier in the class are related to this, and can I remember and explain those concepts?”

Self-testing, a form of retrieval practice, is seeing how much can be remembered without looking at notes, textbooks, or other materials. Testing yourself works because you have to make an effort to retrieve the information from your brain, something we don’t do when we passively review our notes or reread the textbook. Each time you retrieve, your memory of the information becomes stronger. Along with this, self-testing can help you avoid the “illusion of knowing” or the “I think I know it” by showing you the gaps in your memory or understanding. This feedback about what you do and do not (yet) know can help you focus your efforts leading up to an exam. Try to retrieve the information from memory at first, and then use your resources (class notes, textbooks, websites) to fill in the rest.

Some effective ways to self-test include:

Also, explaining concepts to others (or even out loud to yourself) is extremely effective. Why? Because when we are trying to explain something to someone else, it’s an opportunity for retrieval practice. Every time we try to go back and pull information from when we are first exposed to it, to now, it interrupts the forgetting and improves retention.

REMEMBER: IF YOU CAN TEACH THE INFORMATION EFFECTIVELY AND ACCURATELY, THEN YOU KNOW IT!

Interleaving

This aspect of practice is more about the how. Interleaving is a learning strategy that entails mixing up the kinds of problems, equations, or scenarios during your practice session. For example, if you use interleaving while preparing for an exam, you can mix up different types of questions, rather than study only one type of question at a time. Interleaving assists with retrieval, and also helps to avoid the trap of familiarity or illusion of knowing. For example, if you do 10 of the same kinds of problems during one study session, you become comfortable with the process, and the familiarity sends the message, “I know this stuff.” Interleaving different kinds of problems (like shuffling a deck of flashcards) forces the brain to consider context: “which rule or procedure to I use in this situation?”

What is test anxiety?

Test anxiety is a feeling of agitation or distress. Test anxiety may be a physical or mental response you experience, such as feeling “butterflies in your stomach,” an instant headache, or sweaty palms during an exam. Some causes of test anxiety are:

- Perfectionism

- Fear of failure

- Overstating the importance of exams

- Fear of disappointing others

- Focusing excessively on the outcome, rather than on effort and improvement (“I need to get a 90 on this exam or I won’t get a C- in the class.”)

- Having unrealistic performance expectations

- Poor preparation

- Lack of skills necessary for success

- Linked to performance anxiety

Anxiety may cause you to have physiological, behavioral, or even a psychological effect:

- Physiological – rapid heartbeat, knot in stomach, headache, tension, profuse perspiration

- Behavioral – indecisiveness, “going blank,” inability to organize thoughts or concentrate

- Psychological – feelings of nervousness, restlessness, or continual doubt, lack of motivation

Test anxiety vs. unpreparedness anxiety

Test anxiety is NOT the same as doing poorly on a test because your mind was focused on something else such as a break-up, upcoming game, or favorite TV show, etc. Feeling anxious about a test because you did not adequately prepare for it is called unpreparedness anxiety.

Unpreparedness anxiety can be avoided by:

- Improving study habits

- Managing time effectively

- Attending tutoring

- Attending review sessions

- Seeing your professor during their office hours

- Taking advantage of help labs and drop-in tutoring

- Prioritizing (“I can’t go hang out with friends until I get XYZ complete.”)

- Using a to-do list

- Setting goals

- Creating weekly study plans and study schedules

Not sure where to start? Talk to someone in the Learning Commons to learn what resources are available to you. Peer Academic Coaches are also available to help you get organized for classes, provide guidance on study techniques and strategies, and/or help you contact your professor if needed.

Strategies for managing test anxiety

Before the exam…

- Be prepared! Use AGILE strategies, including the Semester-at-a-Glance to start preparing for your exam early and often.

- Mimic the testing environment as often as possible. The best way to prepare for an exam is to test yourself ahead of time. Why not do that in the same way you’ll be tested on exam day?

- Sit in a quiet, distraction-free space.

- Tip: Is part of your anxiety related to the classroom environment? Find an empty classroom to practice in.

- Only have the items you’ll be using in the exam (pencil, calculator, bottle of water, etc).

- Leave your notes in your bag!

- Set a timer for the length of time you’ll have to complete the exam. This gives you a sense of urgency and simulates the class period you’ll be taking the exam in.

- Sit in a quiet, distraction-free space.

- Surround yourself with positive people who also want to succeed on the test. Consistently studying with those who make negative comments will only increase your anxiety.

- Keep a journal or diary – write down any anxiety inducing thoughts on a piece of paper to clear your head (and track your symptoms too).

As the exam approaches…

- Get plenty of sleep the night before an exam.

- Trouble sleeping?

- Try breathing/visualization exercises: use your mind to visualize something that is calming and relaxing for you.

- Try a sleep app on your phone.

- Trouble sleeping?

- Be sure to eat something beforehand that’s healthy and can provide you with good energy. If you’re “hangry” during an exam, you won’t be as focused as you should be.

- Avoid excess caffeine; you may already be feeling jittery and too much caffeine will increase those feelings.

- Do something relaxing the hours before the test, if you’re able to; avoid last-minute cramming!

- Wear something comfortable.

- Get to the exam early and sit somewhere away from distractions! Nothing exacerbates anxiety like being late. Arriving early allows you time to sit quietly, relax, and get focused.

During the exam…

- Take deep breaths.

- Try “square” or “box” breathing: breathe in for 4 seconds, hold the breath for 4 seconds, exhale through the mouth for 4 seconds.

- Picture positive images of a scene you find peaceful.

- Read the instructions thoroughly before beginning the exam.

- If you freeze up or your mind “goes blank,” take a couple of minutes to free-write about the problem or question just to get your mind going.

- If you feel stuck, skip that question and move on to the one that you can answer. Working on another problem may jog your memory so you can go back and complete the problem you had trouble with.

- Think about a post-exam reward. What is something fun you will do after the exam?

What else? Consider exploring the following external resources:

- How to Beat Test Anxiety Video (9:02) (Thomas Frank)

- Taming Your Test Anxiety (Oregon State University)

If you find yourself struggling with anxiety, despite our tips, please be sure to explore the resources available to you through USM’s Health and Counseling Services.

When you receive a graded exam back from your professor, what do you do with it? Many students spend a considerable amount of time preparing for exams, but often do not take the time to reflect on exam information, giving no further thought to the exam other than the grade received. Critically reviewing an exam can yield useful information to help you grow and develop as an independent learner.

Analyzing returned exams can help you understand why you made errors so that you can adjust your approach the next time you are assessed. If your goal is to improve your performance, you will need to review the evaluation carefully, not just for content (the correct answers), but more importantly, for what was not effective about your preparation. Developing an appreciation for the fact that you lost points as the result of how, what, and when you studied, all elements within your control, will suggest the changes necessary to produce improved results on your next evaluation.

Our Post-Exam Review video features a step-by-step guide for completing a post-exam review, which includes timely strategies for improving your performance the next time you are assessed. If your professor does not return exams, consider making an appointment to discuss your exam during office hours. Remember, this is an opportunity to improve future performance and discover more about your own learning process!

Video: Introduction to Mind Mapping

Preparing for Final Exams

Related Exam Preparation Webpages:

Additional Exam Preparation Resources:

*Return to the Study Skills & Learning Strategies homepage